1.1 The 16th century, miniaturists and British artists in Holland

Portrait painters were constantly in great demand in England. For the first 70 years of the 16th century portraits had been commissioned mainly from foreign, i.e. Flemish and Dutch, artists. Local artists were mentioned for the first time in the Elizabethan era (1558-1603). The Queen even preferred ‘British-born artists’ such as Nicholas Hilliard (c. 1547-1619) and George Gower (c. 1538-1596).1 Indeed, her portrait could only be painted by certain artists – the very best, of course – and the resulting image would then serve as a model to be copied by other artists working in two or three large picture factories.2 Hence there was precious little scope for the ‘artists’ to take a subjective approach in the portraits they produced. The conquests and persecutions initiated by the Duke of Alba forced many members of the Reformed Church to flee to England, including artists and craftsmen from Antwerp and other places in Flanders.3 Marcus Gheeraerts II (1561/2-1636) from Bruges was one of the best among them and he felt very much at home in England.4 His portraits have a certain significance for us, since they show that he gradually adopted the painting style of Dutch portraitists who worked in England during the reign of Charles I (ruled 1625-1649).5 The pre-eminent Dutch painter under Elizabeth I (1558-1603) was Cornelis Ketel (1548-1616), who was active in London from 1573 until about 1581. He is undoubtedly identical with the painter named Cornelius who is mentioned in Wits Commonwealth.6 Ketel’s major works include the 1577 portrait of Martin Frobisher (Bodleian Library, Oxford) [1] and the portrait that he made in 1579 of William Gresham (Granville Leveson-Gower collection, Titsey Park) [2]. Regrettably, his portrait of Queen Elizabeth has not survived. His concept of portraiture is recognisable in many English pictures dating to around 1600 (portrait of Michael Drayton, National Portrait Gallery, London, 776; portrait of Phineas Pett, ibidem no. 2035; of John DeCritz I ?) [3-4].7 Together with a series of other lesser-known native artists, Cornelis Ketel, Marcus Gheeraerts II and Federico Zuccaro (1539/43-1609)8 represent the late Mannerist type of portrait in England, which replaced the style favoured by Anthonis Mor (1516/21-1576/7).

1

Cornelis Ketel

Portrait of Martin Frobisher (1535?-1594), dated 1577

Oxford (England), Bodleian Library (University of Oxford), inv./cat.nr. LP 50

2

Cornelis Ketel

Portrait of William Gresham (1522-1579), dated 1579

Private collection

3

Anonymous England dated 1599

Portrait of Michael Drayton, dated 1599

London (England), National Portrait Gallery, inv./cat.nr. 776

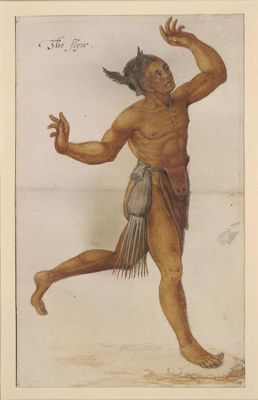

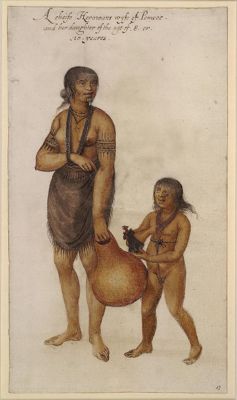

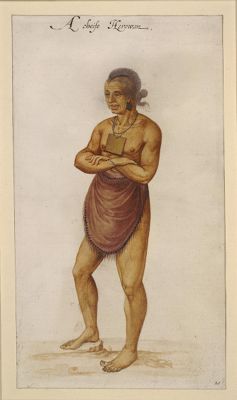

A specifically English style was most readily apparent in the field of portrait miniatures, in which Isaac Oliver (c. 1565-1617) and Nicholas Hilliard attained a considerable mastery. In his figurative drawings, on the other hand, Oliver was an out-and-out Mannerist and barely distinguishable from Dutch artists such as Joachim Wtewael and Maerten de Vos [5-6].9 The Flemish element was more noticeable in his work than the Dutch. A brief mention must be made here of John White (c. 1540-after 1593). Although not a miniaturist as such, he nonetheless incorporates various aspects of the work of such artists. Very well-known are his watercolours of indigenous people whom he saw in Virginia [7-10]. One is tempted to think that his vibrant images were influenced by Dutch models. However, it would be hard to find such early examples of Dutch watercolours. Evidently the artist’s own observation of nature rendered superfluous any imitation of the Dutch artists’ realistic depiction of people and landscapes.10

4

Anonymous England c. 1612

Portrait of Phineas Pett (1570-1647), c. 1612

London (England), National Portrait Gallery, inv./cat.nr. 2035

5

Isaac Oliver

Moses striking water from the rock, c. 1600

Great Britain, private collection The Royal Collection, inv./cat.nr. RCIN 913529

6

Isaac Oliver

A revel with satyrs and nymphs in a forest clearing, c. 1605-1610

Great Britain, private collection The Royal Collection

7

John White (c. 1540-1606)

The Flyer, c. 1585-1586

London (England), British Museum, inv./cat.nr. 1906,0509.1.16

8

John White (c. 1540-1606)

A Cheif Herowans Wyfe and her Daughter, 1585-1586

London (England), British Museum, inv./cat.nr. 1906,0509.1.13

9

John White (c. 1540-1606)

A Cheif Herowan, c. 1585-1586

London (England), British Museum, inv./cat.nr. 1906,0509.1.21

10

John White (c. 1540-1606)

An indigeous huntsman, c. 1585-1586

London (England), British Museum, inv./cat.nr. 1906,0509.1.12

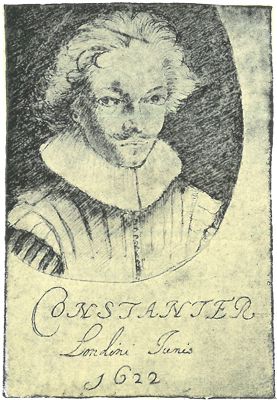

In connection with these English miniaturists, reference can be made to two Dutchmen who broadly followed their example. In 1594, Jacques de Gheyn II (1565-1629) engraved the portrait of George Clifford, Duke of Cumberland [11],11 thereby documenting his familiarity with English miniature painting. He need not necessarily have been in England at this time, but there are more detailed reports of a later sojourn in the company of Constantijn Huygens I (1596-1687) and Jacques de Gheyn III (1596-1641). Huygens, who knew the miniaturist Isaac Oliver and owned a number of his works, was joined by de Gheyn on a visit to Prince Henry’s gallery and to the Arundel Collection, after which they proceeded together to Oxford. That was in 1618. Four years later de Gheyn was back in London, as is apparent from the remains of a sketchbook containing views of Hampton Court [12] and other places.12 We will return to his ‘English’ works later on, in a different context. Constantijn Huygens also made a number of drawings during the trip. In June 1622, he immortalised himself through a self-portrait in an Album Amicorum (friendship book) [13].13 The other Dutch miniaturist to appear in England at the start of the 17th century was the adventurer Balthazar Gerbier d'Ouvilly (1591-1663). He made a portrait of the young Charles I in 1616 when the latter was Prince of Wales [14]. Gerbier, who subsequently returned to England on several occasions, enjoyed excellent relations with the court and the aristocracy. He accompanied Charles I on his unsuccessful search for a bride in Spain in 1623. At the behest of Buckingham and the royal family, he was also active as a picture dealer and political secret agent. His miniatures are pictures in the manner of Hendrick Goltzius and de Gheyn, both of whom he must have known [15].14

11

Jacques de Gheyn (II)

Portrait of a man wearing sash, dated 1594

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-1913-2540

12

Constantijn Huygens (I)

Self-portrait of Constantijn Huygens (1596-1687), dated June 1622

Private collection

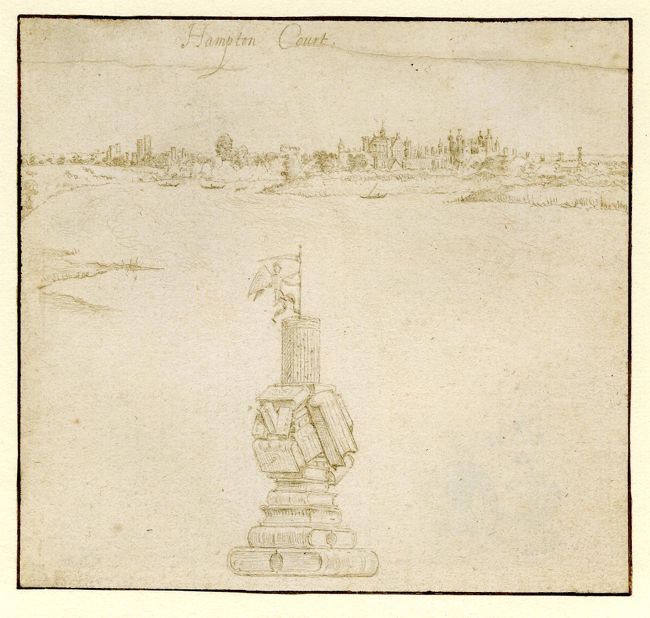

13

Jacques de Gheyn (III)

View of Hampton Court, a sundial in the foreground, 1618-1627

London (England), British Museum, inv./cat.nr. 1850,0223.190

14

Balthazar Gerbier d'Ouvilly

Portrait of Charles I (1600-1649) as Prince of Wales, ca. 1616

London (England), Victoria and Albert Museum, inv./cat.nr. P.47-1935

15

Balthazar Gerbier d'Ouvilly

Portrait of Charles I (1600-1649) as Prince of Wales, dated 1616

London (England), Victoria and Albert Museum, inv./cat.nr. 621-1882

During the reign of James I, and even more after the accession to the throne of the artistically inclined Charles I, a new wave of Netherlandish portraitists made their way to England. Best known among them were Paulus van Somer, Daniel Mijtens I, Gerard van Honthorst and Hendrick Pot. Henry Peacham was rather offended by this acclamation for non-British artists: ‘I am sorry that our courtiers and great personages must seeke far and neer for some Dutchman or Italian to draw their pictures, our Englishmen being held for Vaunients [= good for nothing]’.15 The court and the nobility definitely preferred artists from abroad. They set great store by a painter’s taste and skill and, in particular, by his modernity. Once Mijtens was in vogue, no one was interested in the older Gheeraerts anymore, and when van Dyck appeared on the scene Mijtens was eclipsed.

At the beginning of the 17th century, several English artists were apparently sent to Holland to learn from their Dutch counterparts. In 1613, for instance, a certain Nataniel Austyn (born c. 1597) studied in Amsterdam under a little-known artist named Jan Teunissen (born 1589). Tobias Franck (c. 1574-1602), a painter from England, was mentioned as being in Amsterdam around 1600, and the same was true a little later of an Esaias Wilbout (c. 1583-1644) ‘van Noorwitz, schilder’ [= of Norwich, painter]. Jeffery Sillemans (died 1646) was made a citizen of Amsterdam in 1610, while a Willem Bertram (born c.1594) was married in Amsterdam in 1623. He was a draughtsman in the manner of Hendrick Potuyl and Pieter Quast [16].16

16

Willem Bertram

Study with soldiers playing dice

Notes

1 [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] This is not entirely the case: she sat to a number of overseas-trained painters, including Cornelis Ketel, Federico Zuccaro and the painter of the ‘Darnley’ portrait (National Portrait Gallery); the portrait by Ketel seems not to have survived. The ‘Sieve’ portrait of the Queen, now in the Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena, was long thought to be Ketel’s portrait of her, but when it was conserved in 1988 it was found to be signed by Quinten Massijs II (RKDimages 302196).

2 [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] While it may have been true that attempts were made to limit painting the Queen’s image to a few chosen artists, in reality this seems not to have been controllable. Copies were made of copies of royal images by a diverse range of artists, many of whom are now unidentified. A number of painters, with studios, were operating in London.

3 [Gerson 1942/1983] For Elizabethan art, compare: Collins Baker 1912, vol 1, p. 75; Cust 1903; L.C (ust) and W.G. C(onstable) in the introduction of London 1926. [Hearn/Van Leeuwen 2022] Cooper et al. 2015.

4 [Gerson 1942/1983] Poole/Cust 1913. [Hearn/Van Leeuwen 2022] For Marcus Gheerarts II: Hearn/Jones 2002. In fact, Marcus Gheeraerts II was brought to London as a small boy in 1568, and seems to have been trained within the Netherlandish exile community there; his first definitely identified works date from 1592.

5 [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] By the beginning of the reign of Charles I, in 1625, Gheerearts II was in his sixties and may almost have stopped painting. Perhaps Gerson was referring to Gheeraerts’s self-portrait of 1627, which is only known from an etching by Wenzel Hollar dated 1644 (RKDimages 261454).

6 [Gerson 1942/1983] The Catalogue of the Rijksmuseum identified this Cornelius as Cornelis de Zeeuw. [Hearn/Van Leeuwen 2022] Van Riemsdijk 1934, p. 327. For Wits Commonwealth, see Meres 1598, p. 288. In his dissertation on De Zeeuw, Wim Luyckx agreed with Gerson that ‘Cornelius’ here did indeed refer to Cornelis Ketel and not to De Zeeuw, who never visited Britain (Luyckx 1999, p. 7-8). However, British art historians now presume that this ‘Cornelius’ was yet another, now unknown, painter (see for example, Cooper 2012, p. 44). For new insights on Ketel: Hearn 2013.

7 [Gerson 1942/1983] See W. Stechow in Thieme/Becker 1907-1950 and Stechow 1929-1930. Stechow conversely speaks of Ketel’s connection with modern English portraiture. [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] These two essentially minor portraits are by unidentified painters.

8 [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] In reality Federico Zuccaro spent only a few months (in 1575) in England, and produced very few portraits there. This fact was not realised when Gerson was writing. See, for example, Goldring 2005.

9 [Gerson 1942/1983] Cundall 1933, p. 356. [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] For John White, see Sloan et al. 2007.

10 [Gerson 1942/1983] Drawings e.g. in the British Museum. Compare London 1934, p. 46; Binyon 1924-1925; Hind 1933, p. 371; M. 1938, p. 21. [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] Sloan et al. 2007.

11 [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] The traditional identification of the sitter as George Clifford 3rd Duke of Cumberland (1558-1605) is not generally now accepted. Van Regteren Altena proposed the name of Adriaan Metius (1571-1635), based on the cryptogram and the depicted comet, but this is not convincing either (Van Regteren Altena 1936, p. 8-9).

12 [Gerson 1942/1983] Van Regteren Altena 1936, p. 8-9, 15-16, 27, 64, 79-79, 114.

13 [Gerson 1942/1983] Moes 1900.

14 [Gerson 1942/1983] De Boer 1903; Hirschmann 1920. Image of Charles I in Williamson 1918, p. 65. [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] Keblusek 2003.

15 [Gerson 1942/1983] Peacham 1634, The Epistle Dedicatory, no pagination (https://archive.org/details/gri_33125008547412/page/n9/mode/2up). [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] See Harding 2009.

16 [Gerson 1942/1983] Bredius 1935; Obreen 1877-1890, vol. 2, p. 275; Bredius 1915-1921, vol. 3, p. 1093-1094; De Vries 1886, p. 300; De Vries 1885, p. 63; sale Leipzig (Ehlers), 27 November 1935, no. 437.