1.3 Honthorst, Poelenburch and Pot

Gerard van Honthorst (1592-1656) [1] travelled to London in 1628 together with his student Joachim von Sandrart (1606-1688).1 Again it was Sir Dudley Carleton (1573-1632), the English ambassador to The Hague from 1616 to 1625, who drew the attention of the English court to Honthorst.2 In 1621 Carleton commissioned the artist, who had just returned from Italy, to produce an Aeneas Fleeing from Troy. He gave the painting as a gift to Lord Arundel, who was delighted with it. This picture, which is no longer extant,3 may have been painted in the style of Caravaggio, as in all probability was the other painting that Honthorst offered to a certain Edward, Clerk of the Council, in a letter of 22 May 1630, intimating that it was a night-time scene. That same year in Utrecht work was in progress under Honthorst’s supervision on a large series of scenes from the Odyssey, which again had been commissioned by Carleton. Each of the eight pictures was to cost 200 guilders, and the artist was at pains to explain to the customer that this was a favourable price. However, there is no clear indication whether the paintings were ever delivered.4 This post-dated Honthorst’s stay in England, which lasted just a few months from April to December 1628. At that time, he concentrated on painting portraits in the manner of Mijtens, who was still in England. Needless to say, he made portraits of the king and queen as well as of other prominent figures such as George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham (1592-1628), who was assassinated in August of that year (portrait in the National Portrait Gallery) [2-3].5

1

Paulus Pontius (I) after Anthony van Dyck

Portrait of Gerard van Honthorst (1592-1656), c. 1632

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum

2

studio of Gerard van Honthorst

Portrait of George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham (1592-1628) with his family, c. 1628

London (England), National Portrait Gallery, inv./cat.nr. 711

3

Gerard van Honthorst

Portrait of George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham (1592-1628) with his family, 1628

Great Britain, private collection The Royal Collection, inv./cat.nr. RCIN 406553

Honthorst received further commissions from the English court after returning home.6 He portrayed the king and his queen as Apollo and Diana in the clouds in a very large picture that is now in Hampton Court [4].

The portrait of the Winter Queen had found its way into the collection of Charles I a few years earlier. It must have been painted before 1627, in other words before Honthorst went to England, because it was engraved that year by Frans Brun (the original is now also at Hampton Court) [5-6].7 Honthorst’s visit to England was probably facilitated by a recommendation from the Winter Queen (1596-1662). She was the sister of Charles I and from 1621 lived with her family in Rhenen, where she and her children took lessons in painting from Honthorst.8 The artist delivered several portraits of her English relatives dressed as shepherds.9

4

Gerard van Honthorst

Apollo and Diana, dated 1628

Hampton Court Palace (Molesey), Royal Collection - Hampton Court, inv./cat.nr. 405746

5

Anonymous England c. 1632-1650

Portrait of Elizabeth Stuart (1596-1662), Electress Palatine, Queen of Bohemia, c. 1632-1650

Great Britain, private collection The Royal Collection, inv./cat.nr. RCIN 404015

6

Frans Brun

Portrait of Elizabth Stuart, called the Winter Queen (1596-1662), dated 1627

Elizabeth also employed Cornelis van Poelenburch (1594/5-1667) from Utrecht as a portraitist, to paint her seven children in 1628. Van Poelenburch probably made several copies of this picture, one of which was sent to England, where it remains to this day (at Hampton Court; another copy is in Budapest) [7-8].10 It may have been through her intervention that Poelenburch went to London in 1637, where he was kept extremely busy. According to Arnold Houbraken, however, he had hardly returned from Italy (in 1626) before he was asked by Charles I to come to England, where he was paid handsomely for his work.11 At all events, Van Poelenburch was in Utrecht in 1627, and his stay in England in 1637 was probably not all that long either.12 Claude Vignon, for his part, suspects that in 1641 the artist was still in London, where his much sought-after works could easily be purchased.13 Be that as it may, Poelenburch’s small, delicate paintings were evidently just as popular in England as they were on the Continent. James II (1633-1701) later owned 16 of them,14 while Charles I, the Duke of Buckingham and many other prominent figures also held the artist’s works in high regard.15 Van Poelenburch’s collaboration was much sought after by various fellow artists, too. He painted the staffage in pictures by Hendrik van Steenwijck II (1580-1640) and Bartholomeus van Bassen (c. 1590-1652), for example.16

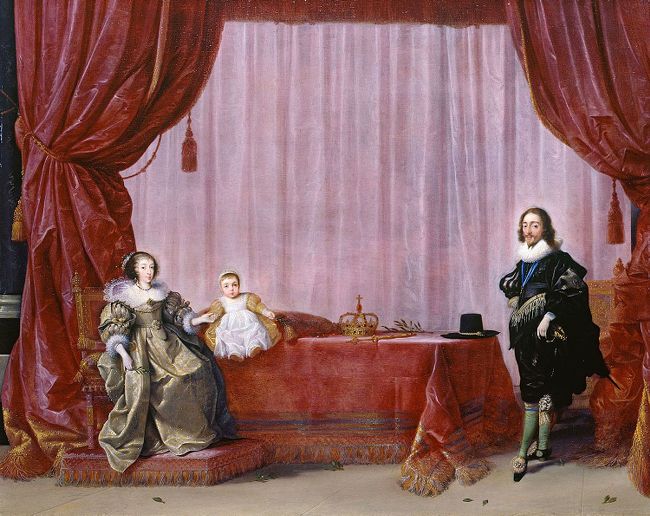

Among the same group of Dutch/English court artists was Hendrick Pot (c. 1580-1657), who was in London between 1631 and 1632. As well as painting portraits of Charles I and his wife and a number of other dignitaries (Louvre, Buckingham Palace) [9-10], he received a royal commission to make a memorial painting of the coronation of Maria de’ Medici – a ceremony that had taken place more than twenty years earlier [11].17 The works of Pot and Van Poelenburch, as well as those of Gerard ter Borch II (1617-1681), who must have been in London in around 1635,18 are representative of the small, delicate type of portrait. That Pot’s style was still quite similar to that of Mijtens is confirmed by the fact that in the past Pot’s portrait of the royal couple was attributed to Mijtens. Pot had a penchant for placing his figures in or against an architectural setting that Hendrick van Steenwijck is said to have painted for him.19 At this stage there was little to be seen of the influence of van Dyck’s art in the work of either artist.

7

after Cornelis van Poelenburch

Portrait of the seven children of Frederick V of Bohemia, Elector Palatine (1596-1632) and Elizabeth Stuart (1596-1662), c. 1628

Holyroodhouse (Edinburgh), Royal Collection - Holyroodhouse, inv./cat.nr. 403558

8

Cornelis van Poelenburch

Portrait of the seven children of Frederick V of Bohemia, Elector Palatine (1596-1632) and Elizabeth Stuart (1596-1662), dated 1628

Budapest, Szépmüvészeti Múzeum, inv./cat.nr. 381

9

Hendrick Pot

Portrait of King Charles I of England (1600-1649), dated 1632

Paris, Musée du Louvre, inv./cat.nr. 2525

10

Hendrick Pot

Portrait of the family of King Charles I of England (1600-1649), 1632-1633

Great Britain, private collection The Royal Collection

11

Hendrick Pot

The coronation of Maria de' Medici (1575-1642) as Queen of France, 13 May 1610, c. 1632

London (England), art dealer Johnny Van (London) Haeften

Notes

1 [Gerson 1942/1983] Sandrart/Peltzer 1925, p. 22, 25, 180, 247; Hoogewerff 1917.

2 [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] On Carleton’s use of works of art: Hill 1999.

3 [Hearn/Van Leeuwen 2022] Judson/Ekkart 1999, p. 106.

4 [Gerson 1942/1983] Carpenter 1844, p. 179; Sainsbury 1859, p. 268-269, 290-291, 294-295.

5 [Hearn/Van Leeuwen 2022] Early copy after the prototype in The Royal Collection. Judson/Ekkart 1999.

6 [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] See Frederick 2019.

7 [Gerson 1942/1983] Other paintings of Elizabeth of Bohemia are at Chatsworth (Strong 1901, no. 46) and at Coombe Abbey, from the collection of William, Earl of Craven, who is said to have secretly married the Queen Dowager of Bohemia (Walpole et al. 1762/1876 [ed. Wornum, vol. 2, p. 7). [Hearn/Van Leeuwen 2022] The portrait at Hampton Court to which Gerson refers is no longer attributed to Honthorst; no alternative attribution has yet been suggested. White/de Sancha 1982/2015, p. 192-193, no. 82, ill. The portrait at Chatsworth (RKDimages 304694) is now attributed to Daniel Mijtens I (not supported by Ter Kuile 1969). The portrait formerly at Coombe Abbey is now in the National Gallery, London (RKDimages 281406).

8 [Gerson 1942/1983] Sir Dudley Carleton had taken the Winter King and his family in to his house in The Hague in 1620, which was an expensive pleasure for him. It was then that Elizabeth first came into contact with Honthorst and with other Dutch artists who were employed by Frederik Hendrik.

9 [Hearn/Van Leeuwen 2022] Gerson refers to two sets of half-length portraits of Charles I and Henrietta Maria as a shepherd and shepherdess, one of which was retained by Charles while the other was sent with Honthorst to Elizabeth (no longer extant). Judson/Ekkart 1999, p. 296-297, nos. 4416 and 418; Frederick 2019, p. 316-317.

10 [Hearn/Van Leeuwen 2022] The canvas in the Royal Collection (now at Holyroodhouse) is a good 17th-century copy of an original, which is known through two versions on panel (Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest and Castle Museum, Anholt) both of which are monogrammed and dated 1628, and both of which bear a Charles I brand-mark on the reverse. The painting in Budapest is considered to be the best version and the one in Anholt an autograph replica. As well as the painting in the Royal Collection, which may have been acquired following the Restoration in 1660, two further copies are known.

11 [Hearn/Van Leeuwen 2022] Houbraken, 1718-1721, vol. 1, p. 129; Horn/Van Leeuwen 2021, vol. 1, p. 129. See also Sluijter-Seijffert 2016, p. 34-35.

12 [Hearn/Van Leeuwen 2022] Poelenburch stayed in London with interruptions between 1637 and 1641; Arnout van Buchel wrote in his diary that Poelenburch travelled back from Utrecht to England on 12 August 1638 (Van Campen 1940).

13 [Gerson 1942/1983] See p. 63, 64. [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] In his chapter on France, Gerson mentions the well-known letter that Vignon wrote to François Langlois when the latter was travelling in England and the Dutch Republic (e.g. Moes 1894).

14 [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] Gerson derived this information from Von Wurzbach 1906-1911, vol. 2 (1910), p. 336-338, who quoted Walpole (Walpole/Vertue et al. 1762/1876, vol.1, p. 342-343). Because the collection of Charles I was dispersed after his death, most of the paintings listed at the time as by Poelenburch are no longer in the Royal Collections, apart from two paintings in the style of Poelenburch which are now at Hampton Court (RKDimages 304740 and RKDimages 304741). See also Sluijter-Seijffert 2016, p. 24.

15 [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] The name of Buckingham (who was murdered in 1628) in this context is clearly a mistake.

16 [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] Poelenburch collaborated with Herman Saftleven and painted figures in landscapes by Alexander Keirincx (who was his neighbour in London), Jan Both, Guilliam de Heusch, Adam Willaerts, and possibly by Chaerles de Hooch; in interior scenes by Bartholomeus van Bassen, Dirck van Delen, Nicolaes de Ghiselaer and Hendrick van Steenwijck II; in still lifes by Philip van Thielen (Sluijter-Seijffert 2016, p. 27-28. and Appendix V, p. 284-288).

17 [Gerson 1942/1983] Schretlen 1919/1920, p. 198; Bredius/Haverkorn van Rijsewijk 1887, p. 163, 171.

18 [Gerson 1942/1983] Moes 1886, p. 146. Lugard 1936, p. 136-137. There are however no known pictures from his English period. [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] Gerard ter Borch II spent three months in the London studio of his step-uncle, the engraver Robert van Voerst (1597-1635) who worked closely with Anthony van Dyck. Ter Borch may have left London because of the plague: his uncle died of the disease and was probably the 'Robert van Vorst a Dutchman' who was buried at St Clement Dane's on 17 September 1635 (Fleming 2014, p. 178). Gerard ter Borch II’s portrait drawing of Van Voerst, which shows the influence of Van Dyck, must have been made in London (RKDimages 304780).

19 [Hearn/Van Leeuwen 2022] This remark seems to confuse Pot with Daniel Mijtens I, who did indeed collaborate with Hendrick van Steenwijck II, e.g. on RKDimages 143630.