2.1 History painting and artists from Utrecht

We will pass by the Mannerist images of Cornelis Ketel (1548-1616) and his successors, since they arose before the specifically Dutch expansion began.1 Pioneering the new dawn was Hendrick Goltzius (1558-1617), whose engravings were also sold in England.2 When homage was paid to James I as King of England in London in 1604, the Dutch community did not wish to be seen as dragging its feet and so it had a triumphal arch erected by Conraet Jansen (c. 1543-after 1604) [1] which was painted by Daniël de Vos I (1568-1605) and Paulus van Overbeeck II. We know nothing else about these two artists; they might have been painters who fled from the southern Netherlands.3

More reliable information is available on Adriaen van Nieulandt (c. 1586/7-1658), who delivered a painting for Ham House in 1615 which is still there today [2]. The Earl of Holderness, then the owner of the house, commissioned a companion piece showing Caesar in his Tent from Jacques de Gheyn II (1565-1629) who, as we will recall, made his way to London at this time [3].4 Both these pictures were among the earliest non-Mannerist figure paintings made by Dutch artists for English clients. Cornelis Drebbel (1572-1633), one of the most talented pupils of de Gheyn and Goltzius, made regular visits to England. In his artistic work he concentrated solely on ‘perspective’ and engravings.5 James I was so impressed by the great variety of his creations that he granted him an annual salary. Works by Abraham Bloemaert (1566-1651) were regularly among the figure paintings ordered from Holland by customers in other countries, England being no exception in this respect. The Earl of Arundel (1585-1646), for instance, received some paintings by Bloemaert in 1629, but regrettably we know nothing about their content.6 Elisabeth of Bohemia (1596-1662), who held the painter in great esteem, visited him in 1626 and ordered a picture of her dog, which she presented as a gift to Sir Dudley Carleton (1573-1632).7 The Danish artist Francis Clein (1582-1658), who arrived in England in 1622, was employed at a weaving mill in Mortlake in 1625. We will return to him later, but it is clear that he cannot automatically be included among the Dutch-trained artists, particularly since he studied in Venice. Be that as it may, there are many points of contact in his oeuvre with the art of the so-called pre-Rembrandtists.8

Since Charles I employed various portrait painters from Utrecht at his court, it seems reasonable to assume that some genre images from Utrecht were to be found there, too. The fact that the Utrecht Caravaggists had connections with the world of Italian art must have been a strong recommendation in itself, since Charles greatly admired Italian paintings, as is evidenced by the works in his collection. Orazio Gentileschi (1563-1639), who belonged to the same group of artists, likewise worked for the English court.9 Gerard van Honthorst (1592-1656) not only painted portraits for English customers; it was under his aegis that work began on the great Odysseus series, which was certainly ‘Utrechtian’ in character. Various of his genre paintings from Utrecht have been discussed above.10 A genre painting by Honthorst is described in the catalogue of the collection of the Duke of Buckingham (1592-1628) as ‘a large piece of a tooth drawer with many figures’ [4].11 In other words, pictures of this kind really were to be found in English collections. Charles I also owned a painting by Hendrick ter Brugghen (1588-1629) [5].12 Louise Hollandine (1622-1709), Honthorst’s pupil, sent her uncle Charles I a picture of Tobias with the Angel together with various portraits.13 Another aspect of Utrecht art is represented by Cornelis van Poelenburch (1594/5-1667), whom we mentioned earlier when looking at the Dutch portraitists. Whether his landscapes with ruins and mythological staffage were painted in England or dispatched later from Utrecht is of little consequence. Charles I owned a whole series of them [6-7].14 The same taste is evident from the Italianate landscapes Charles I acquired from Bartholomeus Breenbergh (1598-1657). In his inventory they are referred to slightly incorrectly as works by a certain Bartholomea.15 Joachim von Sandrart reports that an ‘Englishman’ by the name of Cornelis Stoop (Stopp) painted caverns and grottos from a strange perspective. In Dresden a grotto in the manner of Abraham van Cuylenborch I was attributed to this otherwise completely unknown artist. Could it be that he also came from Utrecht? Judging by the description of his works they would fit in well with the group under discussion here.16

1

Willem Kip after Stephen Harrison after design of Conraet Jansen published by John Sudbury and George Humble

The Pegme of the Dutchmen, dated 1604

London (England), British Museum, inv./cat.nr. 1981,U.3018

2

Adriaen van Nieulandt

Diana with nymphs, dated 1615

Richmond (Greater London), Ham House, inv./cat.nr. NT 1139668

3

Jacques de Gheyn (II)

Julius Caesar on horseback, writing and dictating simultaneously to his scribes, c. 1618–1622

Richmond (Greater London), Ham House, inv./cat.nr. NT 1139674

4

Gerard van Honthorst

The Dentist, dated 1622

Dresden, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden - Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, inv./cat.nr. 1251

5

Hendrick ter Brugghen

Bass viol player with a glass, dated 1625

Great Britain, private collection The Royal Collection, inv./cat.nr. RCIN 405531

6

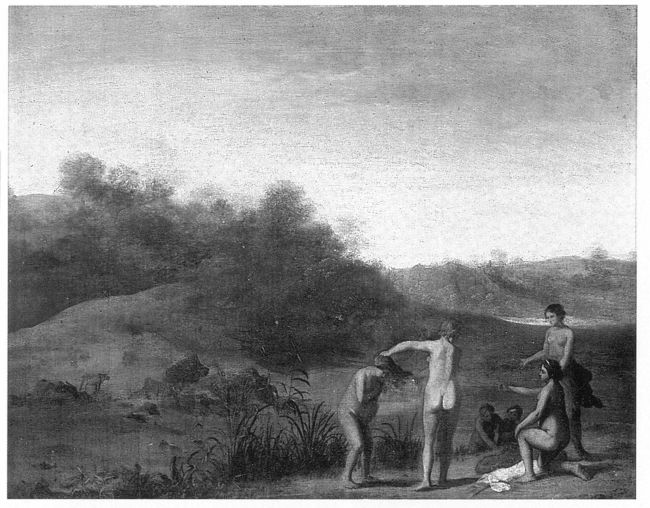

Cornelis van Poelenburch

Landscape with ruins and a herd of goats

London (England), art dealer Agnew's

7

Cornelis van Poelenburch

Landscape with Diana and Callisto, c. 1640

London (England), art dealer Agnew's

Notes

1 [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] Obviously, in the 1930s, when Gerson wrote his text, Dutch Mannerism was not considered to be real Dutch, which essentially is true as Mannerism is an international style. The revaluation by art historians for Dutch Mannerism developed from the 1970s onwards.

2 [Gerson 1942/1983] Bredius 1914, p. 139.

3 [Gerson 1942/1983] Toorenenberg/Ruytinck et al. 1873, p. 190. [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] Conraet Jansen was from Breda; Daniel de Vos I and Paulus van Overbeeck II were both from Antwerp. For more about the commission of the triumphal arch for the entry of James I in 1603/4: Jansen 1604; Hood 1991; Grell 1996, p. 165-174; Hood 2003, p. 46-51.

4 [Gerson 1942/1983] Van Regteren Altena 1936, p. 27, pl. 4. [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] De Gheyn II may have painted the picture either for Sir Thomas Vavasour (1585-1620), the first owner of Ham House, or his successor, John Ramsay, Earl of Holderness (c. 1580-1626). Two figures from the composition were copied by De Gheyn’s son, Jacques de Gheyn III when he was in London (RKDimages 305774). Van Regteren Altena 1983, vol. 2, p. 16-17, no. 13, pl 6; p. 180, no. S 7, pl. 7. The similar framing to the work by van Nieulandt does not point to an early acquisition, as van Regteren Altena claims: the framings date from the 1670s (Rowell 2013, p. 155, fig. 137).

5 [Gerson 1942/1983] Naber 1904. [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] About his activity in Britain (mostly as an inventor, not as an engraver): Harris 1961.

6 [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] A set of paintings of the Four Evangelists by Bloemaert was recorded in the collection of the Earl of Arundel in 1655, as well as a St. Peter in Prison (Hervey 1921, p. 476, nos. 37 and 40). Not mentioned in Roethlisberger/Bok 1993.

7 [Gerson 1942/1983] Sainsbury 1859, p. 293, note 24. [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] Roethlisberger/Bok 1993, vol. 1, p. 113114, no. 68.

8 [Gerson 1942/1983] See Gerson 1942/1983, p. 454, 461. [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] Gerson/Van Leeuwen/Roding et al. 2015, § 2.2 and § 4.2.

9 [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] See Wood 2000-2001.

10 [Gerson 1942/1983] See Geron 1942/1983, p. 372-373. [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] See § 1.3.

11 [Gerson 1942/1983] Fairfax/Talman 1768, p. 20. The catalogue only describes the small part of his paintings that was sold during the exile in Antwerp.[Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] Judson/Ekkart 1999, p. 210-212, no. 275, ill.

12 [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] Millar 1958-1960, p. 49, no. 41, p. 205, 231; White 1982, p. 31, no. 83, pl. 22; White/De Sancha 1982/2015 , p. 118-120, no. 33, ill.

13 [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] Vertue/van der Doort 1649/1757, p. 53, no. 71. See also index card of Cornelis Hofstede de Groot: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/excerpts/230334 and https://rkd.nl/en/explore/excerpts/230333.

14 [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] Sluijter-Seijffert 2016 , nos. 117 and 220. A history painting by Poelenburch (Adoration of the Magi) in Charles I’s collection was RKDimages 290330).

15 [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] Vertue/van der Doort 1649/1757, p. 14, no. 52; Roethlisberger 1981, p. 92, no. 242. Not known today.

16 [Gerson 1942/1983] Sandrart/Peltzer 1925, p. 349. Compare also Hofstede De Groot 1893, p. 300. Hofstede de Groot (index card) doubts the existence of the painter. He is probably identical with Dirk Stoop, who came to England in 1662 (see Gerson 1942/1983, p. 217 and 382) and who painted such cave paintings (Hamburg, Göttingen). [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] Indeed the Cornelis Sto(o)p mentioned by Sandrart is now considered to refer to Dirk Stoop, see his profile on Sandrart.net. The painting in Dresden went missing in World War II, see no. 133860 on Lostart.de. For Stoop in Gerson’s chapter on Germany: Gerson/Van Leeuwen et al. 2017-2018, p. 2.3. For more about the genre of grotto or cavern paintings: Rosen 2013.