2.2 Landscape, marine and architecture painting during Charles I

The reference above to Bartholomeus Breenbergh (1598-1657) takes us on to landscape painters. Among the works Charles I owned was one by Roelant Savery (1576-1639) [1]. Active in London in 1640/41 was Alexander Keirincx (1600-1652), whose connection with the Utrecht school is obvious, even though he hailed from Flanders. Poelenburch occasionally painted the staffage in his paintings.1 According to Walpole, Keirincx had allegedly been to London once before in 1625, having been commissioned by the king to paint views of Scottish castles; he is said to have made drawings in London, too [2-3].2 In Charles’s inventory his name is spelt Carings.3

Keirincx’s Flemish-Dutch landscape style set a trend in England. Anonymous English (?) landscapes in Cambridge (no. 61: The Old Palace at Richmond; no. 95: Nonsuch Palace) [4-5] drew on Keirincx’s style, while the view of Old Pontefract Castle in Hampton Court may have been done by his own hand [6]. A copy purportedly by Joos de Momper II was exhibited at the Country Life exhibition in 1937 [7].4 The paintings in Cambridge have also been attributed to David Vinckboons I although, as far as we know, he was never in England.5 The same artist could have painted a view of the Tudor Palace at Greenwich, which is now in the Maritime Museum in Greenwich (Queens House, Room 2, no. 2) [8]. Another member of the same group of Flemish-Dutch landscape painters was Adriaen van Stalbemt (1580-1662), whose views of Greenwich were seen by Walpole in English collections [9].6 There is every reason to doubt whether all these artists really were in England. On the other hand, the considerable number of Flemish-Dutch landscapes which can still be seen in England today would indicate that various landscape artists did spend some time in the country. The view of the Thames at Greenwich in the Bruce S. Ingram Collection, which the owner attributes to Wenzel Hollar, also belongs to this group [10].7

1

Roelant Savery

Mountainous landscape with resting lions, dated 1622

Great Britain, private collection The Royal Collection, inv./cat.nr. RCIN 405627

2

attributed to Alexander Keirincx

View of the Thames and the Tower of London from the Bermondsey side, 1637-1641

London (England), British Museum, inv./cat.nr. 1855,0714.60

3

Alexander Keirincx

A view of the Thames at Whitehall, c. 1638-1641

Oxford (England), Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology, inv./cat.nr. WA.Suth.B.1.262.18

4

Anonymous, Flemish or British

The Thames at Richmond, with the Old Royal Palace, 1620s

canvas, oil paint 152.1 x 304.2 cm

Cambridge, Fitzwilliam Museum, inv.nr. 61

5

Anonymous, Flemish or British

Nonsuch Palace, 1620s

canvas, oil paint 151.8 x 302.5 cm

Cambridge, Fitzwilliam Museum, inv.nr. 95

6

Anonymous British or Flemish, possibly after Alexander Keirincx

View of Pontefract Castle from the south-east, c.1625-1630 or ca. 1633

canvas, oil paint 115.6 x 106 cm

Hampton Court, inv.nr. RCIN 404974

7

Anonymous, Flemish or British, or attributed to Alexander Keirincx

View of Pontefract Castle, c. 1633 or c. 1640-1641

canvas, oil paint 106 x 182 cm

Pontefract, Pontefract Museum, inv.nr. A1.93

8

Anonymous, British

Greenwich from the south-east showing the Park and Tudor palace, c. 1620

canvas, oil paint 29 x 63.5 cm

Greenwich (London), Royal Museums Greenwich, inv.nr. BHC1820

9

Adriaen van Stalbemt

View of Greenwich from the south-east, c. 1632-1633

Great Britain, private collection The Royal Collection, inv./cat.nr. RCIN 406578

10

Anonymous, British or Netherlandish

View of the river Thames at Greenwich, c. 1635

panel, oil paint 30 x 91,5 cm

London/Cambridge/Chesham, collection Sir Bruce Stirling Ingram (1938)

11

Anonymous

A view of Westminster, London (?)

paper, pen, brown wash, inkt 90 x 285 mm

Paris, Fondation Custodia - Collection Frits Lugt

Of greater interest here are the young Dutch artists who went to England. As far as we can see, none of them succeeded in obtaining any official commissions. They had to content themselves with sketchbook notes instead. Claes Jansz. Visscher’s (c. 1586/7-1652) ‘’t Income van London te Westminster’ in the Lugt collection [11],8 Marten de Cock’s (1578-1661) rare drawings [12]9 and Jacques de Gheyn III’s travel memos of 1622 all fall into this category. The latter made drawings in Hampton Court amongst other places and produced a copy of two figures from his father’s painting of Caesar [13-14].10 The only instance of a landscape painter being mentioned as court painter is Cornelis Hendriksz. Vroom (c. 1590/92-1661) in 1628.11 However, since he signed an official document in Haarlem in July 1629, he cannot have stayed in the country for very long.12 Or did he merely supply pictures from Holland? At all events, there is no evidence so far of any works he might have made at such an early date. Among the artists who can be included, with a certain reservation, among the Dutchmen in England was Wenzel Hollar (1607-1677). He hailed from Prague and was apprenticed in Frankfurt and Strasbourg; copies he made after Jan van de Velde II have survived from the time of his apprenticeship there [15].13 These confirm what can be deduced anyway from his many landscape drawings, namely that his style of drawing was largely moulded by the generation of naturalistic artists from Holland. The Earl of Arundel met him in Cologne in 1636, took him along on his travels and in 1637 went with him to England, where the artist remained – with the exception of an extended stay in Antwerp (1644-1652) – until his death.14 Hollar certainly played a major role as a communicator of the Dutch approach to art, particularly since he was also a very prolific draughtsman and etcher.

12

Marten de Cock

Landscape with castle and bridge, dated 23 July 1630

Frankfurt am Main, Graphische Sammlung im Städelschen Kunstinstitut, inv./cat.nr. 5539

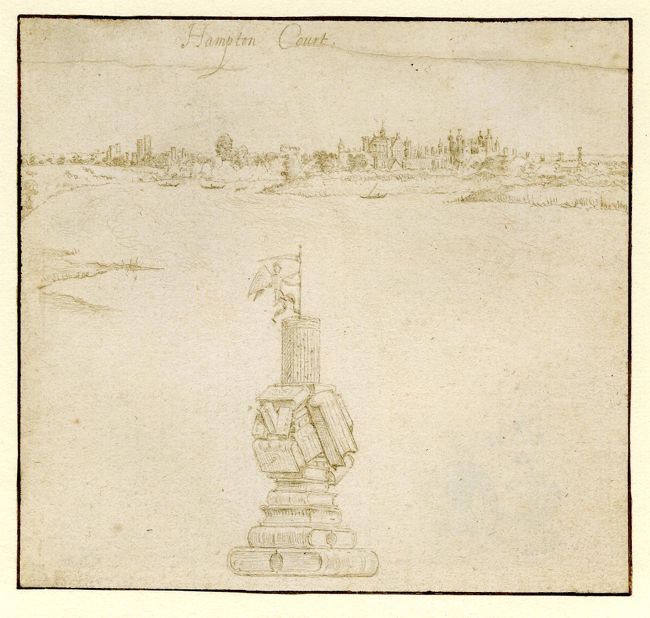

13

Jacques de Gheyn (III)

View of Hampton Court, a sundial in the foreground, 1618-1627

London (England), British Museum, inv./cat.nr. 1850,0223.190

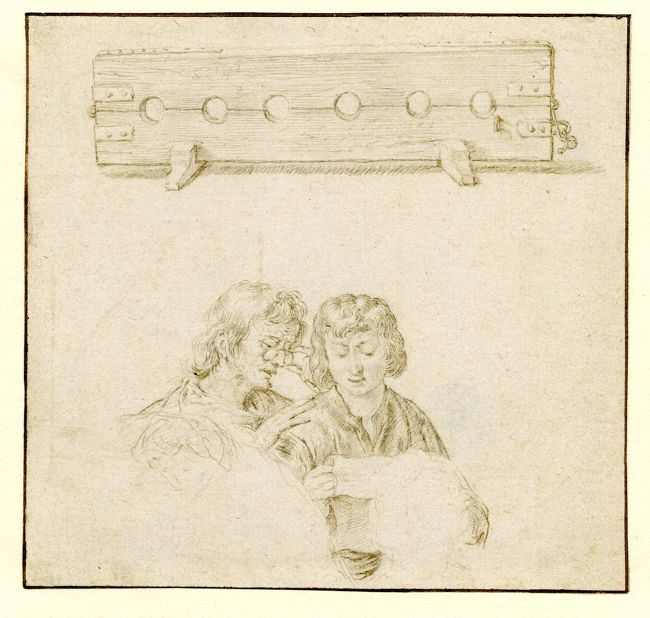

14

attributed to Jacques de Gheyn (III) after Jacques de Gheyn (II)

A pair of stocks, and below, two men reading a document, c. 1618-1627

London (England), British Museum, inv./cat.nr. 1850,0223.191

15

Wenzel Hollar after Jan van de Velde (II)

Spring, in or shortly before 1629

Schloss Ehrenburg (Coburg), Kunstsammlungen der Veste Coburg, inv./cat.nr. Z 395

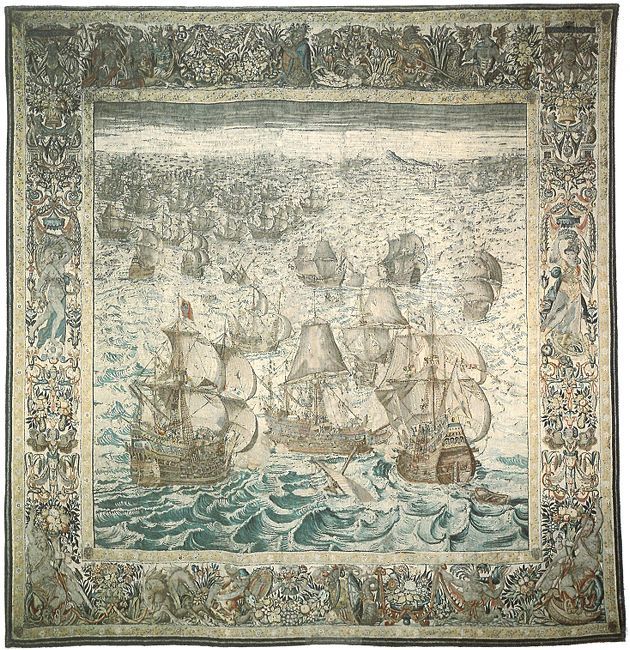

The Dutch marine painters who worked at the English court merit special attention. Karel van Mander I recounts in great detail the adventurous life of Hendrik Vroom (1562/63-1640), the father of the aforementioned Cornelis. The tapestry weaver François Spiering (1551-1630) needed a draughtsman to design the cartoons for a series of tapestries illustrating the victories of the English navy over the Spanish Armada which Charles, Lord Howard of Effingham, had ordered from him in 1592.15 Karel van Mander felt he was not up to the task and so he arranged a meeting between Spiering and Hendrik Vroom, who handled the commission superbly. Queen Elizabeth I tried in vain to have the tapestries presented to her as a gift. While they did later come into possession of the crown, they ultimately perished in a fire in the Palace of Westminster [in 1834]. The only tapestry to have re-emerged (original or copy?) entitled The Revenge [16].16 Vroom was not a pattern drawer by profession and must therefore be counted among the random designers. He paid several visits to London and, after introducing himself to Lord Howard on one occasion, received not only the agreed fee for his work but also a gift of money.17 The English miniaturist Isaac Oliver (c. 1565-1617) took this opportunity to paint his portrait [17].18

Vroom remained in contact with the English court. He was commissioned – no doubt from the highest quarters – to paint Charles I’s return from Spain and his arrival in Portsmouth in 1623 (collection of the Earl of Sandwich, currently on loan to the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich) [18]. A copy of the painting from the collection of Charles I, which was sold by the Commonwealth government in 1651, was later returned to the royal collection and is now in Hampton Court (no. 876) [19].19 Earlier, in 1610, the Staten van Holland had acquired from Vroom the Battle of Gibraltar and Storm at Sea for the princely sum of 1,800 florins so that they could be offered to the ‘Prince van Whalis’ (Prince Henry who, like his brother, the later Charles I, must have been an avid collector) ‘wiens successie seecker ende wiens vriendschap deze landen noodich is.20 Adam Willaerts (1577-1664) and Cornelis Claesz van Wieringen (1575/7-1633) also appear to have painted for Charles I and Henry, since the royal yachts frequently feature in their works. It is unlikely that they were ever in England themselves, however.21

Two paintings by Jan Porcellis (1584-1632) (‘Persellis’) are listed in the inventory of Charles I’s collection [20-21], a third being sold from his confiscated possessions in 1649. As Sir Lionel Preston has quite rightly observed, this latter work depicting a naval battle is one of the first realistic scenes of its kind [22].22 Indeed, it is not at all improbable that Porcellis was in England himself, since a ‘Jaquemyntjen Porcellis, jongedochter van London’ married an Antoni van Delden in Leiden in 1629.23 She was in all probability a daughter of the painter, given that a grandson of the artist was called Jan Porcellis van Delden.24 Various members of the Flessiers family were mentioned as being in England. Willem Flessiers (died 1670), Tobias Flessiers (1610-1689), Elisabeth Flessiers and Balthasar Flessiers II (c. 1605-1681?) were all in the country in 1637.25 Tobias seems to have been the marine painter referred to by Sanderson (Art of Painting, 1658) and Walpole. Charles I and Peter Lely owned some of his paintings while others were in the old collection in Ham House.26 Walpole also said that Flessiers painted still lifes and taught Marcellus Laroon I (c. 1648/9-1702), which is not out of the question, since the painter was still registered as being resident in London in Dutch certificates issued in 1663. We are not familiar with the seascapes by Gillis Schagen (1616-1668) referred to by Arnold Houbraken.27 It seems there were still no native English marine painters at this time.28

16

Heyndrick de Maecht after design of Hendrik Vroom

The last fight of the Revenge in 1591, dated 1598

Private collection

17

Simon Frisius after Isaac Oliver published by Hendrik Hondius (I)

Portrait of Hendrik Cornelisz. Vroom (1562/1563-1640), 1610 or before

The Hague, RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History

18

Hendrik Vroom or attributed to Frederik Hendriksz. Vroom (II)

The Return of Prince Charles from Spain, 5 October 1623, c. 1624

Greenwich, National Maritime Museum (Greenwich), inv./cat.nr. BHC0710

19

Hendrik Vroom or possibly Cornelis Hendriksz. Vroom (II)

The Return of Prince Charles from Spain, 5 October 1623, c. 1624

Hampton Court Palace (Molesey), Royal Collection - Hampton Court, inv./cat.nr. RCIN 406193

20

Jan Porcellis

Ships in a sotrm before the coast, c. 1610

Hampton Court Palace (Molesey), Royal Collection - Hampton Court, inv./cat.nr. 697

21

Jan Porcellis

Naval battle by night, c. 1610

Hampton Court Palace (Molesey), Royal Collection - Hampton Court, inv./cat.nr. 850

22

Anonymous, Netherlandish

The Battle of Downs, 21 October 1629, c. 1640

canvas, oil paint 122 x 223,5 cm

Hampton Court Palace

This is perhaps an appropriate moment to say something about another special genre: architectural painting. Charles I owned a painting made in 1566 by Hans Vredeman de Vries (c. 1525/6-1609), who died in about 1604 [= 1609], showing Mary and Martha with figures by Anthonie Blocklandt van Montfoort (1533/4- 1583) (Hampton Court) [23].29 Although Vredeman de Vries can be regarded more as a Flemish artist, we draw attention to his painting here because various copies have been made of it, some of which have been attributed to Bartholomeus van Bassen (1590-1652) (Ingram auction, London, 12 March 1926, no. 2) [24].30 The English architectural painter Thomas Johnson (active 1634-1685) also copied the picture (inscribed in full and dated 1658!) [25].31 This is a fine example of the enduring nature of a Dutch model. Other works known to be by Johnson include some rather hesitantly drawn views of Canterbury Cathedral and a number of topographical landscape sketches from the same area, in which he tends to follow the example set by Wenceslaus Hollar [26].32 Charles I also employed Hendrik van Steenwijck II (1580-1640) who spent some time in London in 1618.33 Bartholomeus van Bassen similarly spent a lengthy period in England.34 Amongst other assignments, both these artists were required to paint ‘perspectives’ for portraits by Hendrick Pot (1580-1657), Daniël Mijtens I (1590-1647) and Cornelis Jonson van Ceulen I (1593-1661).35 A work by Gerard Houckgeest (1600-1661) (who must therefore have been in London) was said to have been ‘a prospective piece painted by Houckgest and the Queens picture therein done by Cornelius Jonson – the dress unfinished’ – a painting which has not come down to us [27].36

23

Hans Vredeman de Vries and Gillis Mostaert (I) or possibly Anthonie Blocklandt

Christ in the house of Mary and Martha, dated 1566

Hampton Court Palace (Molesey), Royal Collection - Hampton Court, inv./cat.nr. 283

24

Hans Vredeman de Vries

Christ in the house of Mary and Martha, c. 1566

Bremen, Ludwig Roselius Museum, inv./cat.nr. B 343

25

Thomas Johnson (active 1634-1685) after Hans Vredeman de Vries and after Gillis Mostaert (I)

Christ in the house of Martha and Mary

London (England), W.H. Woodward

27

Cornelis Jonson van Ceulen (I) and Gerard Houckgeest

Portrait of Henrietta Maria of Bourbon (1609-1669), queen of England, c. 1635-1639

Private collection

26

Thomas Johnson (active 1634-1685)

View of Canterbury

New Haven (Connecticut), Yale Center for British Art, inv./cat.nr. B1975.3.154

The king was not only interested in portraitists, landscape, marine and architectural painters, virtually all of whom were mainly employed to paint or reproduce images of his surroundings, people, palaces and state ceremonies on land and water. He was also fascinated by the Utrecht school of painting, the Caravaggists and van Poelenburch’s images of idyllic places. Quite remarkable, too, was his concern for the fate of the imprisoned artist Johannes Torrentius (1588/9-1644). Perhaps Dudley Carleton had a hand in the matter once more. In 1630 Charles wrote to Frederik Hendrik requesting him to effect the painter’s release so that he might travel to London. Torrentius made his way to England in December of that year with a letter of recommendation from the young Dudley Carleton to Lord Dorchester (the former Dudley Carleton). The artist was notorious for his scandalous nude paintings, which the king might have wished to see himself! However, the fame Torrentius enjoyed was attributable primarily to his still lifes, one such being praised by Lord Dorchester as early as 1629. Perhaps it is the same painting that now hangs in the Rijksmuseum and was once in Charles I’s collection [28]. Torrentius was not in England for any great length of time, though. In 1640/41 he was obliged to leave the country after his conduct there had given cause for considerable vexation.37

28

Johannes Torrentius

Emblemetic still life with flagon, glass, jug and bridle, dated 1614

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. SK-A-2813

Notes

1 [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] On the collaboration between Keirincx and Poelenburch: Sluijter-Seijffert/Wolters 2009.

2 [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] Walpole referred to drawings in the sale of the collection Charles d’Agar (1669-1723), one of them ‘a view of the Parliament house and Westminters stairs to the water, dated 1625’, which Vertue, who was present at the sale, attributed to Keirincx (Walpole/Wornum 1876, vol. 1, p. 346). The drawing is however by Claude de Jongh (1606/6-1663), see RKDimages 305816. Hayes 1956, p. 4. Keirincx was documented in London for the first time in 1638, when he was granted a royal pension of £60 per year starting from 25 April 1638 onwards (Wood 2000-2001, p. 125). About Kerinincx royal commission, see Towsend 2003.

3 [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] Vertue/van der Doort 1649/1757, p. 20.

4 [Gerson 1942/1983] Collins Baker 1929, p. 53. no number; London 1937, ill. p. 1 [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] Millar 1963, p. 159, no. 438. Millar considered the version mentioned by Gerson as in the Country Life exhibition (now in the Pontefract Museum as by Alexander Keirincx) as the version which was once in the collection of Charles I; the website of the Royal Collections now considers it the other way around. A third version, closest to the painting in Hampton Court, appeared at sale London (Sotheby’s), 19-03-2003, no. 62 (RKDimages 305836).

5 [Gerson 1942/1983] Walpole et al. 1762/1876 (ed. Wornum), vol. 1, 341, vol. 3, p. 153, notes by Dallaway; Grant 1926, vol. 1, p. 5-6. [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] Grant 1957, vol. 1, p. 38-39. Grant wrongly claims Vinckboons had been in Britain; Dallaway did the same. Elaborating on Gerson, Rubenstein probably rightly calls the paintings in Cambridge ‘Anglo-Flemish School’ (Rubenstein 1994, p. 167 [fig. 11], 169, 177). Harris invented a name for the (in his eyes: Flemish) artist of these pendant paintings: ‘Master of the Flying Storks’ (Harris 1979, p. 24-25, no.s 16-17, ill.).

6 [Gerson 1942/1983] Walpole et al. 1762/1876 (ed. Wornum), vol. 2, p. 19. Also mentioned is a prospect of Greenwich by Portman [= George Portman (died 1649)].

7 [Gerson 1942/1983] Waterhouse et al. 1938, p. 24, no. 26, ill.

8 [Gerson 1942/1983] There is also an engraving by Visscher with the view of London from 1616 [= RKDimages 303699]. [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] Both the attribution and the identication of the subject by Frits Lugt are incorrect.

9 [Gerson 1942/1983] Drawing in Frankfurt of 1630, image in Stift und Feder 1926, no. 30.

10 [Gerson 1942/1983] Regteren Altena 1935, p. 27-28, 97-99, pl. 4. [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] See also above, p. 1.1 and p. 2.1, note 3.

11 [Gerson 1942/1983) On 11 November 1628 be was paid £80 by the court 'for work done and pictures painted' (Carpenter 1844, p. 179). Compare. [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] Other landscape painters who were paid by the court of Charles I were Alexander Keirincx, Bartholomeus Breenbergh and Cornelis van Poelenburch. Wood 2001-2001, p. 124-125.

12 [Gerson 1942/1983] Bredius 1915-1921, vol. 2 (1916), p. 658-659.

13 [Gerson 1942/1983] Springell 1938, p. 36, 49, 111.

14 [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] Hollar arrived in London with Arundel on 28 December 1636 (Springell 1963, p. 94). Apart from long-term visit to the Southern Netherlands, Hollar left England to accompany Lord Henry Howard on his embassy to Tangier in in 1669.

15 [Gerson 1942/1983] Van Ysselsteyn 1936, vol. 2, p. 76. [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] Van der Donk 1994, p. 87-88.

16 [Gerson 1942/1983] Van Ysselsteyn 1936, vol. 1, p. 243- 245. [Hearn/van Leeuwen 1988] Rodríguez-Salgado et al. 1988, p. 279, no. 16.23, ill. (color). The ‘re-emerged’ tapestry was not part of the Armada series, but a separate commission from Lord Thomas Howard, 2rst Earl of Suffolk and 1rst baron Howard de Walden (1561-1626), commander of the expedition on which Sir Richard Grenville and the Revenge were lost. Thomas Howard was a kinsman of Charles Howard, who commissioned the Armada series. The tapestry was most probably woven in Middelburg by Heyndrick de Maecht (Van der Donck 1994). For the whole series of engravings of the Armada tapestries by John Pine (1691-1756): Rodríguez-Salgado et al. 1988, p. 248251, nos. 14.12-14.21.

17 [Gerson 1942/1983] Van Mander/Floerke 1906, vol. 2, p. 272-273. [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] The ‘Lord Howard’ van Mander referred was possibly Thomas Howard, not Charles Howard (see previous note).

18 [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] Although Oliver is usually not mentioned as the inventor of Frisius’ print, he probably was. Van Mander wrote that Vroom, while in London, became acquainted with Oliver, who painted a miniature portrait of him (Van Mander 1604, fol. 288r). Vertue (c. 1713) wrote that the posture and design of the print seems to be after Isaac Oliver. Vertue Notebooks I, p. 154; Finsten 1981, vol. 1, p. 135, ad no. 94.The 18th-century copy after Frisius’s print by Thomas Chambars (RKDimages 305397) does mention Oliver as the inventor.

19 [Gerson 1942/1983] The inventory of the Commonwealth Sales states: ‘done by Young Vroom’. In Moes 1900A, p. 219 as by Cornelis Vroom (see above); Bredius 1915-1921, vol. 2 (1916), p. 652: Frederik Hendriksz. Vroom II (c. 1600-1667), the younger brother of Cornelis Vroom. [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] Also in Russell 1983 as not by Hendrick or Cornelis Vroom, but possibly by Frederik Hendriksz. Vroom II. About the uncertainty of the attributions: White 1982, p. 147; White/De Sancha 1982/2015, p. 426.

20 [Gerson 1942/1983] Unfortunately the Prince of Wales already died in 1612. In Kramm 1857-1864, vol. 6 (1863), p. 1814-1815, the gift was associated with Charles I. Balbian Verster 1922 claimed the gift was intended for James I, not for the Prince of Wales. Furthermore, the States presented two paintings by Vroom. One of them was possibly the painting in Haarlem (no. 300) [RKDimages 8746]: the ship was built by Phineas Pett for Prince Henry (C. Callander in the introduction of Burlington Fine Arts Club 1929, p. 10-11). [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] The painting Gerson suggests cannot have been part of the Dutch Gift of 1610, as it is dated 1623. Van Gelder wrongly identified a painting representing the Battle of Gibraltar in the Rijksmuseum as the painting presented by the States (Van Gelder 1963, p. 544-545); the work appeared to be by Cornelis Claesz. van Wieingen (Russell 1983, 175. 202 (note 2), attribution by R.M. Vorstman). About art as (diplomatic) gifts in the Dutch Republic: Zell 2021, p. 97-163.

21 [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] Nothing confirms Gerson’s speculation about commissions from the English court to Willaerts or van Wieringen. Until 1999 it was thought that Adam Willaerts was born in Antwerp (based on De Bie 1662), but his baptism on 21 July 1577 is registered in the records of Austin Friars, London. His parents came from Antwerp and had settled in London as protestants; in the late 1580s the family moved to the Dutch Republic (Briels 1997, p. 408-409, see also Moens 1884, p. 84 and Nelemans 1999, p. 21).

22 [Gerson 1942/1983] Preston 1937, p. 23. Two other paintings attributed to Jan Porcellis in Hampton Court (in storage) are works by the school of Paul Bril. [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] In this note Gerson mixed up works, referring to the two panels by Porcellis (Collins Baker 1929, p. 166, in storage), while he actually attributed another work, listed as Porcellis in the Royal Collection, to Bril (RKDimages 305903); also in the Visual Documentation Collection as attributed to Paul Bril. The two panels by Porcellis were in the collection of Prince Henry first; the brand ‘HP’ and ‘CR’ appear on the back. They were part of a set of three sea-pieces, of which the third did not survive. De Beer 2013, p. 12-13, 16, figs. 1 and 3; White/de Sancha 1982/2015, p. 286-288, nos. 148-129, ill.. The third painting Gerson mentioned is not attributed to Porcellis anymore. The subject was identified by Robinson as the Battle of Downs, which took place after Porcellis’ death; also, the work cannot be connected to an inventory before 1731 (White 1982, p. 158-159, no. 265). The fact that the was painted much later, explains why Gerson (and Preston) considered it to be ‘one of the first realistic scenes of its kind’.

23 [Gerson 1942/1983] Bredius 1915-1921, vol. 2 (1916), p. 614. [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] See also De Beer 2013, p. 16, 37 (note 32).

24 [Gerson 1942/1983] Thieme/Becker 1907-1950, vol. 27 (1933), p. 269. [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] Porcellis was at least twice with his family in London: in 1606, when his daughter Jacquemijntgen was born (see previous note) and in 1622: his wife Jacquemyntje was buried at St. Botolph without Aldgate on 16 February 1622 (Town 2014, p. 157). On 7 August 1622 Porcellis was back in Haarlem and posted banns with Janneke Flessiers, daughter of the painter/artdealer Balthasar Flessier I (died c. 1626), who was a resident 1618-1621 in St. Botolph without Aldgate. It is likely that Porcellis met Janneke in London (Walsh 1974, p. 658; Town 2014, p. 1570). De Beer surmised that Porcellis was several times in London (De Beer 2013, p. 16).

25 [Gerson 1942/1983] Bredius 1915-1921, vol. 2 (1916), p. 622; Bredius 1906, p. 132. [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] Their sister Anneke or Janneke Flessiers married Jan Porcellis in 1622, see previous note.

26 [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] Bredius 1906, p. 132; Walpole et al. 1762/1876 (ed. Wornum), vol. 2, p. Some of the information could however also refer to Balthasar Flessiers II, as Walpole called him ‘B. Flessiers’ and Balthasar II was probably also still active in London at the time. About Peter Lely’s collection, see Ogden 1943, Ogden 1944 and Dethloff 1999. Three paintings, a landscape and two sea pieces, by ‘Tobie Flesheeres’ and ‘Flesheires’ respectively, were recorded at Ham House, Surrey, in 1683 (An Estimate of Pictures, manuscript at Ham) (Simon 2012/2014).

27 [Gerson 1942/1983] Houbraken 1718-1721, vol. 2 (1719), p. 30. [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022[ According to Houbraken Schagen witnessed the Batlle of Downs (1639) at which the Dutch admiral Maerten Harpertsz. Tromp destroyed the fleet of Antonio de Oquendo. See also Horn/van Leeuwen 2022, p. 31-32.

28 [Gerson 1942/1983] In Meres 1598 a Peter van de Velde is mentioned. Was he was a Dutchman? [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] Peter van de Velde (died 1606) fled Antwerp in 1585 and travelled from Amsterdam to London the same year. Town 2014, p. 181-182, 225, notes 2839-2846.

29 [Gerson 1942/1983] Vuyk 1929, p. 108, fig. 2.

30 [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] Now in the Ludwig Roselius Museum in Bremen. According to Fusenig the copy in the William Ingram sale of 1926 is another copy, but upon inspection of the image in the micro fiches of the Witt Library (RKD), it is seems to be the same version. See Borggrefe/Fusenig/Uppenkamp 2002, 189-190, no. 10, ill.

31 [Gerson 1942/1983] Auction London (Campbell), 29 January.1930, no. 42; image in The Architects Journal 1926.

32 [Gerson 1942/1983] Image of his work in Caröe 1911, p. 352, pl. XL [RKDimages 305873].

33 [Gerson 1942/1983] Hirschmann 1920, p. 112. [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] Steenwijck seems to have been in London from 1613 until about 1629. He may have been in England in 1613, which is suggested by a picture-in-picture in the portrait of the English musician and courtier Nicolas Lanier (RKDimages 305895; Wilks 2010). He met his wife, the artist Susanna Gaspoel (1602/10-1664) in London; their son Hendrick was born in 1632 in Amsterdam. See Fusenig (2021) in Saur 1992-2022.

34 [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] The unfounded claim that van Bassen had spent time in England derives from Kramm (Kramm 1857-1864, vol. 7 [1864], p. 8) and was repeated in Von Wurzbach 1906-1910, vol. 1 (1906), p. 63; not mentioned in later sources.

35 [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] As far as we know, van Bassen collaborated with Esaias van de Velde, Frans Francken II, Anthonie Palamedesz und Cornelis van Poelenburch.

36 [Gerson 1942/1983] At Hampton Court, two architectural pieces are attributed to Gerard Houckgeest - one is dated 1637 [=1635] - which may be identical with other works mentioned in old inventories. They are entirely in the style of Bartholomeus van Bassen; thus early pictures, if the attribution is correct. (Collins Baker 1929, p. 79-80, nos. 627 and 645) [RKDimages 186201 and RKDimages 273300].. [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] The painting by Houckgeest and Jonson van Ceulen mentioned by Gerson did survive and was identified by Millar (Millar 1962, p. 330, fig. 4). However, there is no proof of a stay in England, although Houckgeest must have had good connections to the Court, from whom he possibly also received direct commissions (E. Schavemaker in Saur 2012, vol. 75 [2012], p. 83). White surmised that Houckgeest was in London in 1635 (date on RKDimages 273300), or at some point in the 1630s; see White 1982, p. xxxiii and White/de Sancha 1982/2015, p. 19.

37 [Gerson 1942/1983] Carpenter 1844, p. 192/193; Sainsbury 1859, p. 292, 348-349; Bredius 1909. [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] Torrentius must have returned to the Dutch Republic between 7 November 1640 and 15 September 1642, probably shortly before the last date; the reason was probably that the Civil War broke out and that Torrentius lost his patron (Cerutti 2014, p. 244, note 368). The claim that Torrentius had ‘given more scandal that satisfaction’ in England derives from Walpole (Walpole et al. 1762/1876 [ed. Wornum], vol 1, p. 345), but cannot be substantiated.