3.1 The Art Collection of the Stuarts

Not a great deal can be added to what has already been said about Dutch art in the possession of royalty. The catalogue of the collection of Charles I (ruled 1625-1649) [1] was published by William Bathoe in 1757 on the basis of a list compiled by Abraham van der Doort (c. 1565/70-1640) in 1639. It merely encompasses the paintings in Whitehall and St. James’s Palace together with several others from Hampton Court.1 Pictures in other royal residences such as Somerset House, Greenwich, Oatlands and Wimbledon were not included in the inventory at the time. However, there are other lists, some of which were only partially published. This applies, for example, to the sale of Charles I's possessions during the Commonwealth regime, about which some information can be found in Claude Phillips's book.2 However, these lists are unlikely to significantly increase the number of Dutch names in British collections. We have already drawn attention to virtually all of them: to the portrait painters Paulus van Somer, Daniel Mijtens, Michiel van Mierevelt, Gerard van Honthorst, Cornelis van Poelenburch and David Baudringhem; to the landscape and marine painters; and, finally, to the owners of paintings by Rembrandt and Lievens. Something of a curiosity are the two paintings by Charles I’s niece, Louise Hollandine (1622-1709), who studied under Honthorst.3 Portraits of royal personages were sent back and forth. Daniel Mijtens’ portraits of English rulers went to Poland4 and Gijsbert van Veen’s portraits of Phillip IV [=III] and Margaret were sent to England as a gift in 1603.5 Charles I inherited the collection of the George Villiers, 1rst Duke of Buckingham (1592-1628) [2], but that will not have added greatly to the number of Dutch works in his possession. It should be borne in mind that collectors’ ambitions at the time were directed primarily at acquiring works by the great Italian Renaissance artists, which, incidentally, they also occasionally bought on the Dutch art market.6 Reference is made regularly to the payment of Dutch artists and agents, without it being clear which works were supplied.7 Buckingham placed great faith in Balthazar Gerbier (1591-1663), who purchased a number of very good Italian paintings. On the other hand, the duke had his portrait taken almost exclusively by Netherlandish painters.8 Nicholas Lanier (1588-1666) and the Flemish art dealer, Daniel Nijs (1572-1647), were very helpful to Charles I in acquiring the precious Mantua collection, 9 while Charles’s most loyal gallery administrator was Abraham van der Doort, who had already rendered special service to Prince Henry. In fact, so conscientious was he that he took his own life after failing to find a miniature his master had put in his charge for safe keeping. Later on, under William III (1650-1702), it was again a Dutchman, Robbert Duval (1649-1732) who, as we have seen, was put in charge of the royal collection.

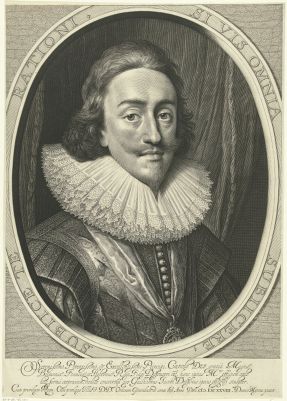

1

Willem Jacobsz. Delff after Daniël Mijtens (I)

Portrait of King Charles I of England (1600-1649), dated 1628

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-OB-50.067

2

Michiel van Mierevelt

Portrait of George Villiers (1592-1628), Duke of Buckingham, c. 1625

Adelaide (Australia), Art Gallery of South Australia, inv./cat.nr. 0.2115

The collection of Dutch paintings did not expand noticeably under Charles II (1630-1665) [3]. His aim initially was to reacquire as much as possible of what had been lost during the time of the Commonwealth government. The Dutch demonstrated great generosity in this respect by offering to make Charles II a gift of the pictures purchased by Gerard Reynst at the auction of Charles I’s possessions – with the added bonus of three works by Gerard Dou [4].10 There was no major increase in the number of paintings Charles II owned, however. Of course, the paintings of his Dutch court painters such as Hendrick Danckerts (1625-1680), Simon Verelst (1644-1713?), Willem van de Velde (1611-1693), Jan Looten (1617/8-1681) and others were listed,11 as were a number of rarities such as five landscapes by Oldenbergh with ‘houses of Prince Maurits in them’ [5-9]. Could it be that the name Oldenbergh applied to a painter in the service of Johan Maurits van Nassau-Siegen (1604-1679)?12

3

Simon Verelst

Portrait of Charles II (1630-1685)

Great Britain, private collection The Royal Collection, inv./cat.nr. RCIN 409151

4

Gerard Dou

Young mother, dated 1658

The Hague, Koninklijk Kabinet van Schilderijen Mauritshuis, inv./cat.nr. 32

5

Oldenbergh

View of the amphitheater in the 'Tiegarten' Cleves, from the north, c. 1670

Hampton Court Palace (Molesey), Royal Collection - Hampton Court

6

Oldenbergh

View of Cleves with the catle seen from Montebello, c. 1670

Hampton Court Palace (Molesey), Royal Collection - Hampton Court

7

Oldenbergh

View of the Butterberg in the Tiergarten, Cleves, from the North, ca. 1670

Hampton Court Palace (Molesey), Royal Collection - Hampton Court, inv./cat.nr. RCIN 406788

8

Oldenbergh

View from the Amphitheatre in the Tiergarten, Cleves, looking North towards Eltenberg, ca. 1670

Hampton Court Palace (Molesey), Royal Collection - Hampton Court, inv./cat.nr. RCIN 406789

9

Oldenbergh

View of the Castle at Cleves looking North, ca. 1670

Hampton Court Palace (Molesey), Royal Collection - Hampton Court, inv./cat.nr. RCIN 406790

James II (ruled 1685-1689) [10] also owned pictures by Philips Wouwerman [11-12], Jan de Braij [13],13 Hendrick ter Brugghen [14],14 Pieter Saenredam [15],15 Willem van Aelst [16]16 and Matthias Withoos [17].17

Printed inventories of the artworks owned by William III do not appear to exist, but we can assume that he extended his collection to include only the works of the contemporary artists we have mentioned.

10

Peter Lely

Portrait of James II of England (1633-1701), c. 1665-1670

London (England), National Portrait Gallery, inv./cat.nr. NPG 5211

11

Philips Wouwerman

A Battle-piece with Soldiers Plundering

Great Britain, private collection The Royal Collection, inv./cat.nr. RCIN 406157

12

Philips Wouwerman

Stacking a hayrick under a stormy sky, ca. 1649

Kensington Palace (London), Royal Collection - Kensington Palace, inv./cat.nr. RCIN 405624

13

Jan de Braij

The banquet of Cleopatra, dated 1652 and 1656/8

Hampton Court Palace (Molesey), Royal Collection - Hampton Court, inv./cat.nr. RCIN 404756

14

Hendrick ter Brugghen

Bass viol player with a glass, dated 1625

Great Britain, private collection The Royal Collection, inv./cat.nr. RCIN 405531

15

Pieter Saenredam

The interior of Saint Bavo's Church, Haarlem, dated 27 February 1648

Edinburgh (city, Scotland), National Galleries Scotland, inv./cat.nr. NG 2413

16

Willem van Aelst

Still life of fowl and hunting equipment on a marble table, dated 1657

Hampton Court Palace (Molesey), Royal Collection - Hampton Court, inv./cat.nr. RCIN 403984

17

Matthias Withoos

Forest still life with otter and two fish, dated 1665

New York City, art dealer Lawrence Steigrad Fine Arts

Notes

1 [Gerson 1942/1983] Vertue/van der Doort 1649/1757; Vertue 1768.

2 [Gerson 1942/1983] Phillips 1906, p. 24 (note 3) and 51-54. [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2023] On the sale of the King’s goods: Millar 1972, MacGregor 1989, Brotton 2006.

3 [Gerson 1942/1983] Walpole et al. 1762/1876 (ed. Wornum), vol. 2, p. 5-6 (note 5). [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2023] Idem, vol. 3, p. 204 (note 1). See also Bathoe 1757, p. 53, nos. 70-71 and index cards of Cornelis Hofstede de Groot 230334 and 230333; online in the Royal Collection. The two works are not known anymore.

4 [Gerson 1942/1983] See Gerson 1942/1983, p. 501.

5 [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2023] Pinchart 1860-1881, vol. 1 (1860), p. 284. Gerons derived the information from Von Wurzbach 1906-1911, vol. 2 (1910), p. 742 and copied his mistake, mentioning Philip IV instead of III. There is no trace of these portraits today.

6 [Gerson 1942/1983] Lugt 1936.

7 [Gerson 1942/1983] In 1629-1630, a warrant was issued ‘to pay unto William Jacobs of Delft [= Willem Jacobsz. Delff] the some of £100: for pictures sent unto H. M.’ (Sainsbury 1859, p. 354). [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2023] Willem Jacobsz. Delff was an engraver, not a painter. It is possible that this entry is related to the making of the engraving of king Charles’s portrait after Daniel Mijtens (here Fig. 1). According to the inscription privileges were granted by Charles I himself, and by the Dutch States General for a period of eight years. As far as is known, Willem Jacobsz. Delff never left the Dutch Republic. It is conceivable that the portrait by Mijtens now in Ottawa (RKDimages 302220) was sent to Delft so that the Willem Jacobsz. Delff could engrave it there, after which he sent it back to London. The painting was bought from Sir Cuthbert Quilter (1841-1911) in 1909.

8 [Gerson 1942/1983] Cammell 1936.

9 [Hearn/Van Leeuwen 2023] On the role of Nijs in the sale of the Gonzaga collection: Anderson 2015.

10 [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] See also § 2.7: Mahon identified one of these paintings as the work now in the Mauritshuis, as it was taken back to the Dutch Republic by William III; Mahon 1949, p. 304, note 20; Mahon 1949A, p. 350. Mahon also wrote that the other two paintings were sold by Dou but not necessarily painted by him; one of them may have been a version of Adam Elsheimer’s Mocking of Ceres. Klessman (and others repeating after him) suggested it possibly survived a fire in Whitehall and may be identical to the painting in the Bader Collection (RDKimages 288039).

11 [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2023] Danckerts, Verelst and Looten were not court painters in the strict sense of the word; they were occasionally commissioned by the king.

12 [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2023] The name ‘Oldenbergh’ as the author of the series derives from the inventory of James II's collection of 1688: 'By Oldenbergh - Five large landscapes, with several houses of Prince Maurice's in them' (Vertue [Bathoe] 1768, p. 69, nos. 787-791). According to Marijke de Kinkelder (former curator of the RKD), ’Oldenbergh’ may be identical to Paulus Jansz. van Oldenburch who became a member of the St. Luke's guild in Dordrecht 16 July 1632 and who was recorded in The Hague in 1637.

13 [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2023] Vertue (Bathoe) 1768, p. 68, no. 769. According to White, the painting was probably acquired by Charles II (White 1982, p. 28-29, no. 31, ill.; White/De Sancha 1982/2015, p. 113-116, no. 31, ill.); however, there is no evidence for this.

14 [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] Vertue (Bathoe) 1768, p. 27, no. 303, under 'Terburg' as 'A man laughing with a glas and base violin in his hand'. Actually, the painting was already acquired by Charles I before 1639; after it was sold by the Commonwealth is was returned to the Royal Collection by Sir Peter Lely after 1660 (Collins Baker 1929, p. 140; White/De Sancha 1982/2015, p. 118-120, no. 33, ill.).

15 [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] Vertue (Bathoe) 1768, p. 6, no. 7: ‘By Sanredan. A piece, being the cathedral of Harlem’. The identification of this painting with the Saenredam now in the National Gallery of Scotland was published by Mahon, who was informed by E.K. Waterhouse (Mahon 1950).

16 [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] Vertue (Bathoe) 1768, p. 44, no. 508. According to White, the painting was probably acquired by Charles II (White 1982, p. 15, no. 9, ill.; White/De Sancha 1982/2015, p. 80-81, no. 9, ill.); however, there is no evidence for this.

17 [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] Two paintings by Withoos were recorded in the collection of James II; Vertue (Bathoe) 1768, p. 39, no. 454 and p. 68, no. 768. The latter, RKDimages 307048, already entered the collection shortly after it was painted and was listed in the collection of Charles II. The first, ‘by W. Withoes. A piece with thistles, an otter, and two fishes’, also entered the collection of Charles II (communication ….). It is not anymore present in the Royal Collection. We propose the identification with fig. 17, last recorded in sale London (Sotheby’s), 5 July 1984, no. 356. The full story of this identification had been published in RKDStories, see Van Leeuwen/ Preußinger 2023.