3.2 Other Collectors

1

Simon de Passe after Michiel van Mierevelt published by Compton Holland

Portrait of Thomas Howard (1585-1646), 14th Earl of Arundel, dated 1616

London (England), British Museum, inv./cat.nr. P,1.57

2

Daniël Mijtens (I)

Portrait of Thomas Howard, 14th Earl of Arundel (1585-1646), c. 1618

London (England), National Portrait Gallery, inv./cat.nr. NPG 5292

Thomas Howard, 2nd Earl of Arundel (1585-1646), referred to by Horace Walpole as the ‘Father of Vertu in England’, was also primarily a passionate admirer of Italian art and antiquity.1 He was in Holland on various occasions, where he endeavoured to have his portrait painted by Michiel van Mierevelt [1] as well as in London, where he approached Daniël Mijtens for the same reason [2].2 The latter assisted him later on in acquiring Italian paintings in Holland. Sir Dudley Carleton (1573-1632) procured other works for him, including a Honthorst, in which the connoisseur of Italian painting will find ‘much of ye manor of Caravagioe’s colouringe’.3 Arundel managed to rescue his possessions by having them transferred to the continent before it was too late. He died in Italy, but large parts of his collection remained in the Netherlands, where the Countess of Arundel (1582-1654) lived. An inventory from around 1655 and an auction in 1684 reveal what he possessed in the way of Dutch paintings in addition to his precious Italian and German works:4 ‘humerous subjects’ by Adriaen van de Venne (1589-1662)5 – probably pictures similar to those John Evelyn (1620-1706) purchased at a fair in Rotterdam in 1641 –,6 some Mannerist depictions, landscapes, seascapes and portraits as well as a ‘small head’ and a drawing by Rembrandt.7 Worthy of particular note at an auction in 1684 were the many works by Jürgen Ovens [3] as well as paintings by Johann Liss II, Johannes Lingelbach [4], Adriaen Brouwer, Jan Both and others.8 Arundel presumably considered the Dutch paintings merely a decorative element in his collection. Once again a Dutchman was his ‘kunstbewaarder’ – Hendrik van der Borcht II (1614-1676), whom Arundel had taken into service in Frankfurt in the course of his journey and subsequently sent to Italy to be trained.9 Should this van der Borcht really be identical with Hendrik van der Burgh, the painter from Delft, as Valentiner surmises, then it is striking to say the least that his works reveal no trace whatsoever of any Italian training let alone a Flemish background.10

3

Jürgen Ovens

Portrait of Queen Christina of Sweden (1626-1689), ca. 1667

Kiel, Kunsthalle zu Kiel

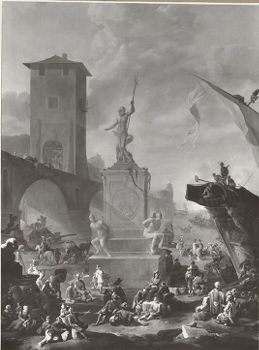

4

Johannes Lingelbach

Southern harbour with a statue of Neptune and slaves (base from the statue of Ferdinando I de' Medici in Livorno), after 1644

art dealer art dealer

Dutch paintings are naturally also to be found among the descendants of the men whose official position required them to remain in the Netherlands for a long time, always assuming they have not been sold and scattered in the meantime. It is conceivable that Sir Dudley Carleton, the later Lord Dorchester, compiled a handsome collection of Dutch paintings over the years, although nothing is known of any such collection or has survived from it. The officers serving under Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester (1532/3–1588) [5] also had their portraits taken by Dutchmen without any pretensions to being art collectors, which is understandable for men who were soldiers.11 On the other hand, the William Craven, 1rst Earl of Craven (1608-1697) [6], who owned Coombe Abbey and was a staunch supporter of Elizabeth Stuart (1596–1662), inherited her portrait collection, which remained in the possession of his heirs for a long time.12

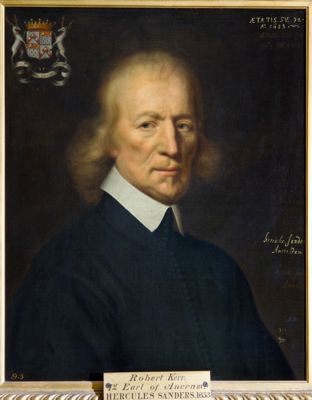

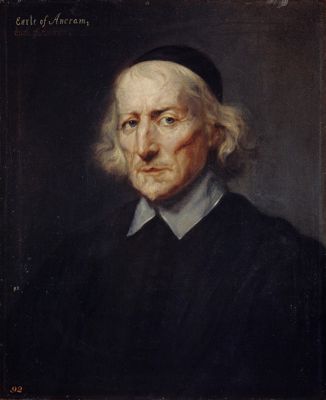

Sir Robert Kerr, the 1st Earl of Ancrum (1579-1655), also acquired his paintings in the course of various journeys through Holland. We have already noted that he made Charles I a gift of three paintings by Rembrandt.13 He had his portrait taken by Hercules Sanders (c. 1606-1666) and Jan Lievens (1607-1674) during his exile in Holland in 1653/4 [7-8]. Works by Dutch still life painters such as Pieter van Roestraten (1630-1700) [9-10],14 Edwaert Collier (1642-1708) [11]15 and Jacques de Claeuw (1623-1694) [12] as well as peasant scenes [13] and other pictures by Lievens [14] are to be found in the possession of his descendant, the Marquess of Lothian, in Newbattle Abbey.16

Towards the end of the century the collections grew rapidly in size and quality. It would exceed our remit to ascertain whether there are any paintings from the earlier art collections still in the possession of the Earls of Radnor,17 Derby,18 Pomfret19 and Elgin,20 of the Duke of Bedford in Woburn Abbey21 or owned by the descendants of William III’s favourite, Hans Willem Bentinck, 1rst Earl of Portland (1649-1709).22

5

Hendrick Goltzius

Portrait of Robert Dudley (1532/3-1588), dated 1586

Birmingham (Great Britain), Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery, inv./cat.nr. 1885C1532

6

Gerard van Honthorst

Portrait of William Craven, Earl of Craven (1608-1697), dated 1642

Cambridge (England), Fitzwilliam Museum, inv./cat.nr. PD 177-1992

7

Hercules Sanders

Portrait of Robert Kerr, 1st Earl of Ancram (1578-1654), at age 72, dated 1653

Private collection

8

Jan Lievens

Portrait of Robert Kerr, first Earl of Ancram (c. 1579-1655), 1654

Edinburgh (city, Scotland), Scottish National Portrait Gallery, inv./cat.nr. PG 3663

9

attributed to Pieter van Roestraeten or Anonymous c. 1650

Still life with musical instruments and hourglass, c. 1650

Edinburgh (city, Scotland), National Galleries Scotland, inv./cat.nr. NG 1937

10

Pseudo-Roestraten

Still life with lute, books and other objects on an oriental tablecloth

Oxfordshire (county), private collection John (Lord) Kerr

11

Edwaert Collier

Vanitas still life with a crown and sceptre, a violin, a jewel casket, a nautilus cup, and a print of Erasmus, dated 1695

Newbattle Abbey, private collection Marquess of Lothian

12

Jacques de Claeuw

Still life with musical instruments, books, flowers and a crucifix, dated 1649

London (England), art dealer Rafael Valls Limited

13

Jacob van Spreeuwen

Old woman and child praying before meal

Leiden, Museum De Lakenhal, inv./cat.nr. 1116

14

Jan Lievens

Praying Capuchin Friar, dated 1629

Private collection

Other figures who are not so well known nowadays, such as the Lord Chancellor John Somers, the banker Sir Francis Child (1642-1713), Robert Spencer, 2nd Earl of Sunderland (1641-1702) and many others, were among the art collectors. Watteau’s patron, Dr. Richard Mead (1673-1754), owned paintings by Dou and Rembrandt.23 The portraitist Sir Peter Lely (1618-1680) not only had a famous collection of drawings but was also a lover of attractive little paintings by Both, Poelenburch, Roestraeten, Wouwerman, Lairesse, Swanevelt, Everdingen and others.24 Reference is made to auctions of Dutch paintings in London in the last two decades of the 17th century, while Dutch art dealers brought large collections to London for sale during the reign of William III.25 We are familiar with a number of these dealers. A certain Jan (John) Pieters (c. 1667-1727) from Antwerp travelled three or four times a year from Holland to London to sell his goods at a profit there.26 It is unlikely that he had only valuable pieces for sale. Another dealer, a Mr. ‘Henry Turner Broome [c. 1683-1733], koopman in schilderijen’ took a ‘meesterschilder’ (= master painter) from Amsterdam with him to England in 1714 ‘om aldaar te schilderen off copiëren’ (=to paint or copy there).27 We also have an illustrative report from the first half of the century in the form of John Evelyn’s diary. In 1642 he travelled to Holland after having had his portrait taken by ‘Vanderborcht servant of Arundel’ [= Hendrick van der Borcht II (1614-1666/7)] [15]. In Rotterdam he was astonished by the huge numbers of ‘landscapes and drolleries’ on offer at the market there. He bought some and sent them to England together with a ‘drollery by F. Covenbergh’, which he acquired a little later in The Hague.28

Those few examples bring us to the end of our brief overview. We can, therefore, now finally turn our attention to Willem van de Velde, one of the most successful Dutch artists in England.

15

Hendrik van der Borcht (II)

Portrait of John Evelyn 1620-1706), 1641 (?)

London (England), National Portrait Gallery, inv./cat.nr. NPG L148

Notes

1 [Gerson 1942/1983] Hervey 1921.

2 [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] See also chapter 1.2. The portrait by Van Mierevelt is only known through by the engraving of Simon van de Passe after Mierevelt of 1616 (illustrated here). Howard probably sat for van Mierevelt in Delft in 1614 (Jansen/Ekkart/Verhave 2011, p. 78), but there is no trace of the original portrait. Hervey mentions a related portrait of Thomas Howard in Boughton House, Northamptonshire; she surmises it concerns a ‘school replica’ after the prototype by van Mierevelt. Hervey 1921, p. 73, pl. VIII; see also Scott 1911, p. 43, no. 106.

3 [Gerson 1942/1983] Hervey 1921, p. 196. [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] Gerson refers to a letter written by Thomas Howard to Sir Dudley Carleton on July 21, 1621 (Sainsbury 1859, p. 291-292; Hervey 1921, p. 196). The painting by Honthorst in Lord Arundel’s letter, representing Aeneas Fleeing from the Sack of Troy, is not known today. Judson/Ekkart 1999, p. 106, no. 89.

4 [Gerson 1942/1983] Cust/Cox 1911 [transcribed copy of the inventory of 1655]; Hervey 1921, p. 473-500 [inventory of 1655 restructured and translated]; Hoet 1752, vol. 1, p. 1-4 [auction catalogue of the paintings of the Earl of Arundel, Amsterdam 1684]. [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] The original inventory of the collection of Thomas Howard and Aletheia Talbot is now lost. However, a copy of this inventory, written in Italian, was produced in Amsterdam in 1655, after the death of the countess of Arundel in 1654. This copy, even though incomplete, was preserved as a part in the volume of proceedings in the English Court of Delegates, forming part of the proceedings in the inheritance litigation between the heirs of the deceased counts of Arundel. The same copy of the original Arundel inventory was found and transcribed by Mary Cox. For the history of the inventory, see also Weijtens 1971, p. 52.

5 [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2023] Hervey 1921, p. 475, no. 10, as: ‘Humorous subjects in chiaroscuro. By A. van Avenne (Adriaen van de Venne)’; Cust/Cox 1911, p. 323, as: ‘Drollerie in Chiaro Scuro’ (possibly produced by Adriaen van de Venne); Cust/Cox 1911A, p. 99, as: ‘Dutch bores reauelling’ (‘Dutch peasants rivalling’). On the subject, see Buijsen 2018, vol. 1, p. 294-294, nos. 3.18-3.21.

6 [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2023] De Beer 1955, vol. 2, p. 39.

7 [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2023] Hervey 1921, p. 487, lists: ‘Rynbrandt (Rembrandt)’, nos. 316 (‘Small Head of a Man’) and 317 (‘A. Old Man. Drawing’). However, Cust/Cox 1911, p. 283, lists: ‘Rynbrandt (Rembrandt)’, ‘Testa d’home in piccolo (Small head of a man)’, ‘St. Gioanni (St. John)’, ‘Donne con capretto et fanciullo ritratto d’homo pregando (Women with goat and portrait of a man praying)’. The mentioned artworks have not been identified.

8 [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2023] Hoet 1752, vol. 1, p. 1-4 (Jürgen Ovens, 18 nos. in total, including the portrait of Queen Christina of Sweden, illustrated here); p. 2, no. 18 (Johann Liss); p. 3, no. 53 (Johannes Lingelbach); p. 3, no. 56 (Adriaen Brouwer). Jan Both is not mentioned.

9 [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2023] In 1636, Count Arundel took the artist Hendrik van der Borcht II into his service, together with Hendrik’s peer and travel companion Wenzel Hollar. Sent to Italy on the Count’s commission, Hendrik van der Borcht II worked for William Petty, one of the art agents of Count Arundel. Along with Petty, van de Borcht operated as an agent for Count Arundel. Harding 1996, p. 39-40. Howarth 1985, p. 183, p. 243, note 50.

10 [Gerson 1942/1983] De Vries 1885, p. 72. Hofstede de Groot 1921, p. 125. Valentiner 1929, p. XXXVII. See also the remark in Gerson 1982/1983, p. 12. [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] Valentiner’s identification of Hendrik van der Burgh (ca. 1625-1664) with Hendrick van der Borcht II (1614-1676) has never been accepted in art historical literature. A review on the confusion between the two artists is provided in Sutton 1980, p. 315.

11 [Gerson 1942/1983] The Earl of Leicester purchased a ‘Deluge’ from Cornelis Cornelisz. (Van Mander/Floerke 1906, vol. 2, p. 310). [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] The painting has not been preserved (Van Thiel 1999, p. 407, no. 289). For the portraits of British soldiers produced in Holland in the social surrounding of Count Leicester, see chapter 1.2, note 18.

12 [Gerson 1942/1983] Several portraits in this collection are depicted in Ward 1903. See also Combe Abbey 1866; sale London (Christie, Manson & Woods), 13 April 1923. [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2023] After the death of William Craven, 4th Earl of Craven (1868-1921), his widow Cornelia, Countess of Craven (1877-1961) sold Coombe Abbey and part of the picture collection. After her death more sales followed: sale London (Sotheby's), 27 November 1968; sale London (Sotheby's), 15 January 1969. On William, 1rst Earl of Craven, see also chapter 1.3, note 7.

13 See chapter 2.3.

14 [Gerson 1942/1983] Hofstede de Groot 1893A, p. 214. [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2023] Hofstede de Groot wrote that he saw no less than six works by van Roestraeten in Newbattle Abbey, some of them clearly marked. References in more recent publications to the works by Roestraten in Newbattle cite the painting now in the National Gallery of Schotland (fig. 9). It was most likely acquired by Robert Kerr, 1rst Marquess of Lothian (1636-1703). Among the six works Hofstede de Groot considered to be by Roestraeten probably was a painting now attributed to an anonymous imitator of Roestraeten which was sold by on 25th June 2019 after the death of Lord John Kerr (1927-2018) (fig. 10).

15 [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2023] The Lothian collection included at least five Collier canvases, one of which was dated 1695 (Wahrmann 2012, p. 175, 248-249, note 12). The 1695 dated work (fig. 11) was sold by the Marquess of Lothian (sale 7/8 December 2016, no. 103).

16 [Gerson 1942/1983] Hofstede de Groot 1893A, p. 214-218. [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2023] Newbattle Abbey was the seat of Henry Schomberg Kerr, 9th Marquess of Lothian (1833-1900) when Hofstede de Groot visited the collection.

17 [Gerson 1942/1983] Walpole et al. 1762/1876 (ed. Wornum), vol. 2, p. 88; Radnor/Barclay Squire 1909. [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2023] E.g. Charles Robartes, 2nd Earl of Radnor (1660-1723).

18 [Gerson 1942/1983] Scharf 1875. [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2023] E.g James Stanley, 10th Earl of Derby (1664-1736); Russell 1987.

19 [Gerson 1942/1983] Fairfax 1758, p. 53-67. [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2023] E.g. Thomas Fermor, 1rst Earl of Pomfret (1698-1753).

20 [Gerson 1942/1983] Hofstede de Groot 1893A, p. 222-224. [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2023] Hofstede de Groot refers to Alexander Bruce, 2nd Earl of Kinardine (1629-1680) and to Thomas Bruce, 7th earl of Elgin and 11th earl of Kincardine (1766-1841). See also Llyod Williams 1992, p. 163.

21 [Gerson 1942/1983] Scharf 1890, p. 118-128. [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2021] The earliest published list of paintings at Woburn dates from 1727 (…). John Russell, 4th Duke of Bedford (1710-1771) started collecting old masters in the 1730s. His son Francis Russell, Marquess of Tavistock (1739-1767) further expanded the collection, as did the latter’s sons, Francis Russell, 5th Duke of Beford (1765-1802) and John Russel, 6th Duke of Bedford (1766-1839). See Waterhouse 1950, Introduction. From 17 June to 24 September 2023 an exhibition was held in the Barber Institute of Fine Arts, Birmingham: Mastering the Market: Dutch and Flemish Paintings from Woburn Abbey (no catalogue).

22 [Gerson 1942/1983] Fairfax 1894.

23 [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2023] The sale of pictures from the Mead collection, 20-22 March 1754, Langford (London), contained two paintings at the time attributed to Rembrandt: a landscape and figures and His own Head. Both works are not known today. The painting listed as by Gerard Dou in the Mead sale concerned a copy after Frans van Mieris’s Boy blowing bubbles in a window and surfaced once more in 1808 (RKDimages 309801).

24 [Gerson 1942/1983] Collins Baker 1912, vol. 2, p. 146-149; Fairfax 1758, p. 43; Monconys 1695, p. 74. [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2023] On the painting collection of Lely: Editorial/Kurz 1943 and Ogden 1944, Dethloff 1996. More recently, attention has been paid to Lely’s drawings collection (e.g. Dethloff 2011); exhibitions in 2009 in Oxford (Christ Church Picture Gallery) and Edinburgh (National Galleries of Schotland), no catalogue.

25 [Gerson 1942/1983] Walpole et al. 1762/1876 (ed. Wornum), vol. 2, p. 83-84 (note 4). [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2023] The note mentioned in Wornum’s edition of Walpole was written by James Dallaway, who referred to advertisements of auctions. In addition to imported paintings from the Low Countries, many works by Netherlandish immigrant artists active in Britain were auctioned in London (Karst 2021, p. 79-105, see also p. 344-345, table 2). The years 1688 to 1693 saw a peak in the number of painting auctions held in London (Karst 2021, p. 88 and p. 343, fig. 5).

26 [Gerson 1942/1983] Weyerman 1729-1769, vol. 3, p. 87. [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2023] Gerson calls Pieters wrongly ‘Nikolaus Pieters’, as Weyerman lists him as ‘N. [= Nomen nescio] Pieters’, not knowing his given name. George Vertue knew Pieters well and called him ‘John Peeters’ (Vertue Note Books III, p. 33).

27 [Gerson 1942/1983] Bredius 1932, p. 128. [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2023] The painter Broome contracted was Friederich (Fredrick?) Hemeling. According to Saur online (accessed October 2023) he was born on 25 February 1685 in Hildesheim and died in the same town on 31 March 1758. As this information was based on a communication of 1975 without a source, this cannot be verified. A Fredrick Hemeling, living in the Eglantierstraat, was buried in Amsterdam on 21 September 1727 in the Karthuizer Kerkhof (City Archive Amsterdam). As no profession is given, is remains uncertain whether this record concerns our painter.

28 [Gerson 1942/1983] Bray 1857, vol. 1, p. 15-16 and p. 20. ’F. Covenberg’ probably refers to the painter Christiaen van Couwenbergh (1604-1667). [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2023] The passage reads: ‘1st September, 1641. I went to Delft and Rotterdam, and two days after back to the Hague, to bespeak a suit of horseman's armor, which I caused to be made to fit me. I now rode out of town to see the monument of the woman, pretended to have been a countess of Holland, reported to have had as many children at one birth, as there are days in the year. The basins were hung up in which they were baptized, together with a large description of the matter-of-fact in a frame of carved work, in the church of Lysdun, a desolate place. As I returned, I diverted to see one of the Prince's Palaces, called the Hoff Van Hounsler's Dyck, a very fair cloistered and quadrangular building. The gallery is prettily painted with several huntings, and at one end a gordian knot, with rustical instruments so artificially represented, as to deceive an accurate eye to distinguish it from actual relievo. The ceiling of the staircase is painted with the ‘Rape of Ganymede’, and other pendant figures, the work of F. Covenberg, of whose hand I bought an excellent drollery, which I afterward parted with to my brother George of Wotton, where it now hangs’. Indeed, ‘F. Covenberg’ can only refer to Christiaen van Couwenbergh, who worked at Huis Honselerdijk (‘Van Hounsler's Dyck’) in 1638. The painting that Evelyn parted with to his brother is not known today.