2.6 Still life painters

This is not the first time we mention Dutch still life painters in England. Charles I had a still life by Johannes Torrentius (1588-1644) (now in Amsterdam) and the marine painter Tobias Flessiers (1610-1689) must also have been active in this field.1 Samuel van Hoogstraten (1627-1678) was one of the first artists to paint trompe l’oeils in England and we know of a fruit still life in the manner of Barend van der Meer painted by the ‘Rembrandt pupil’ Godfrey Kneller (1646-1723) [1].2 And did not Nathaniel Bacon (1585-1627) paint kitchen still lifes in the manner of the earlier painters from Delft?3 According to Arnold Houbraken, Otto Marseus van Schrieck (1619/20-1678) must have been in England, although there are no other sources to confirm this.4 A Pieter van den Bosch (1612/3- after 1663) is mentioned as being in London in 1663. However, since it is not certain whether this artist is identical with the painter of still lifes from Leiden we will not pursue the matter any further here.5 More important are the still lifes by Pieter van Roestraeten (1630-1700), who was introduced to Charles II by Peter Lely (1618-1680) [2].6 In stylistic respects his paintings are still very Dutch. It is only from the English tea service and the medallions with the portrait of Charles II that we realise we are in England [3-4].7 These images cannot be compared with the painterly works of Willem Kalf and Abraham van Beijeren, however. They are far more restrained and content with an objective rendering of nature. Van Roestraten died in London in 1700 and must have worked in England for over thirty years. Interestingly enough, his work had no influence whatsoever on contemporary painters.8 Peter Lely owned some of his paintings, as did many nobles in the country. Even today his works are still frequently on offer at auctions in England.

1

Gottfried Kneller

Still life with nuts, fruit, bread, wineglass, pitcher and carpet on a marble table, dated 1676

2

Pieter van Roestraeten

Vanitas

Great Britain, private collection The Royal Collection

3

Pieter van Roestraeten

Vanitasstilleven met doodshoofd, kunstvoorwerpen, luit en wijnkoeler, dated 1678

Ponce (Puerto Rico), Museo de Arte de Ponce, inv./cat.nr. 67.0621

4

Pieter van Roestraeten

Still life on a marble table with Chinese porcelain, glassware, a violin and a wax seal document

Private collection

Edwaert Collier (1642-1708) probably worked for a time in England. However, we can only refer to a single painting to support that claim [5].9 It is a genuine ‘oogenbedrieger’, an astonishing achievement similar to the works Samuel van Hoogstraten was accustomed to painting in England and elsewhere. There was always a keen interest in such works [6-7].10 Hence it is not really surprising that van Hoogstraten’s endeavours were replicated by other Dutch artists. The landscapist Jan van der Vaart (c. 1653-1727) painted ‘a violin against a door’, a work that Walpole saw in Chatsworth [8].11 There must have been a trompe l’oeil in the Painter-Stainers Hall on which Zacharias Conrad von Uffenbach (1683-1734) deciphered the name Taverner in 1710. But he was not sure whether this was the name of the painter or only an insert designed to further enhance the deception.12 We have no idea either. In conclusion we should like to draw the reader’s attention to a simple still life by the unusually rare Dirck Ferreris (1639-1693), whom Peter Lely summoned to London.13

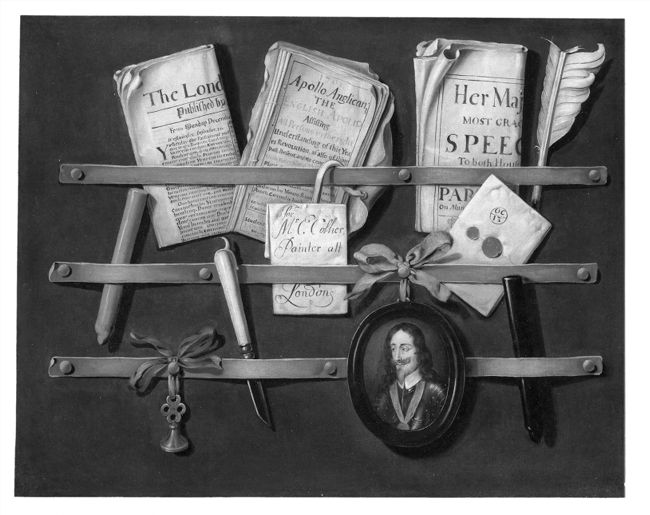

5

Edwaert Collier

A trompe-l'oeil letter rack with writing materials, documents and a medal of Charles I, c. 1701-1702

London (England), Victoria and Albert Museum, inv./cat.nr. P.23-1951

6

Edwaert Collier

Trompe l'oeil with a portrait of Charles I Stuart (1600-1649), King of England, dated 1701

London (England), art dealer Richard Green

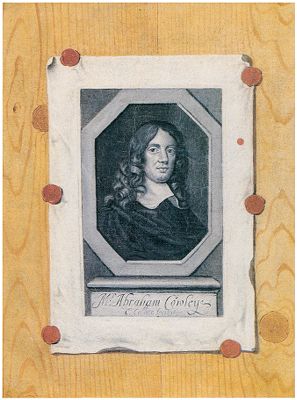

7

Edwaert Collier

Engraving of the poet Abraham Cowley (1618-1667) on a wooden wall, dated 1695

Middlebury (Vermont), Middlebury College Museum of Art, inv./cat.nr. 1996.002

8

attributed to Jan van der Vaart

Trompe l'oeil of a violin and bow hanging on a door

Chatsworth House, private collection Devonshire Collection

It is at this time that the first English still life painters emerge. Oddly enough, they appear to have had no connections at all with their Dutch fellow artists in England, although they certainly did with Dutch still life art. The most famous among these painters was William Gowe Ferguson (c. 1632/3-after 1695). However, as a Scotsman who spent over twenty years in Holland he cannot solely be assigned to the history of British art. His manner of painting was thoroughly Dutch. His images of hunting gear and dead birds form part of a popular genre cultivated by Willem van Aelst, Henri de Fromantiou and other artists with an international focus [9]. Among the exceptional paintings in Ferguson’s oeuvre are a bouquet of flowers in a vase (in the Simon Verelst style) [10] and a group portrait (in the manner of Nicolaes Maes and Johannes Mijtens), although the latter certainly arose in The Hague [11].14 Landscapes with ruins (Edinburgh, and Leningrad, from 1680) [12-13] confirm Walpole’s statement that Ferguson was in Italy.15

9

William Gowe Ferguson

Still-life with dead birds and hunting equipment, daetd 1684

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. A 2154

10

William Gowe Ferguson

Flower still life in a glass vase

11

William Gowe Ferguson

Portrait of two girls and a boy with a goat udner some trees, dated 1660

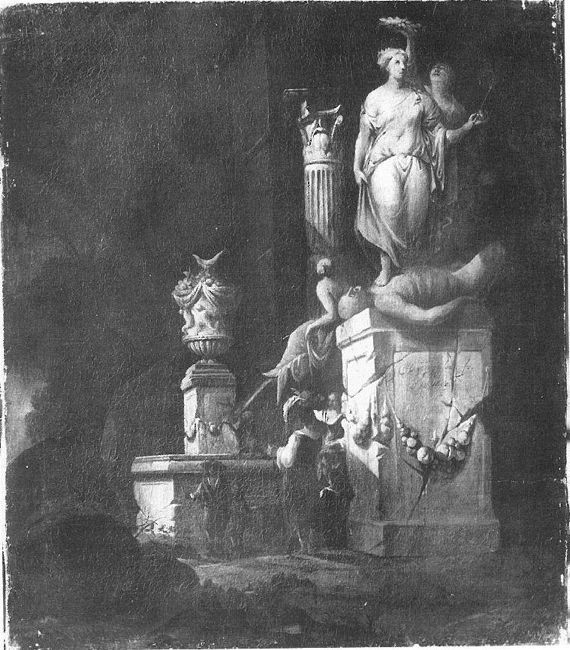

12

William Gowe Ferguson

A ruined alter with figures

Edinburgh (city, Scotland), National Galleries Scotland, inv./cat.nr. 190

13

William Gowe Ferguson

Landscape with ruins, dated 1680

Sint-Petersburg, Hermitage

Among the English paintings in Dulwich College is a still life described in detail in Cartwright’s catalogue of 1686 as a work by ‘Mr. Walton’. Parry Walton (died 1702), who studied under Robert Walker, was the gallery director in charge of James II’s collection. He is known to have been active as a painter of still lifes and also as a copyist. In 1687 he restored Rubens’ ceiling in Whitehall. His son, who is also said to have painted still lifes, succeeded him as director of the royal gallery. The still life in question in Dulwich College looks so Dutch that it could well be attributed to a successor to Willem Kalf such as Pieter Gallis or Juriaan van Streek, although there are also clear associations with the art of Pieter Claesz. [13].16 Could it be that Walton copied a Dutch painting from his master’s collection?17

The Dutch flower painters mark the illustrious end of Dutch influence both in England and elsewhere in Europe. The masters of this art received handsome payment and there was still enough money around for mediocre painters to earn a living. Flower paintings by Jan Davidsz. de Heem (1606-1684) were among the most precious gifts a royal personage could receive. A certain Johannes van der Meer (1630-1695/7) made William III a gift of a floral wreath by the artist for which he paid 2,000 guilders himself – a princely gift indeed! It contained a portrait of the king [14], and the donor clearly expected to derive considerable benefit from his generosity. William III took the painting with him to England without expressing his thanks for the gift in any tangible form.18 Incidentally, his much reviled predecessor James II owned a still life by ‘Deheem’, and Jacob Campo Weyerman (1677-1747) met a fellow artist in London by the name of (N.) de Heem, who was a painter of flowers. This might be Jan Jansz. de Heem (1650-after May 1695), a son of Jan Davidsz. de Heem, who could have been in England around 1710.19 Weyerman’s work earned him a tidy sum in London. The flowers on mirrors he painted for Queen Anne earned him 2,400 guilders alone! When this source of income dried up, he moved to the countryside to enchant rich customers and aristocrats with his art. Nor did he consider it beneath his dignity to insert the bunches of flowers that Godfrey Kneller (1646-1723), John Closterman (1660-1711) and Robert Robinson (active 1674-1706) required in their paintings.20

The biggest demand of all, of course, was for paintings by Jan van Huijsum (1682-1749), who never set foot in England himself. His brother Jacob van Huysum (1688-1740), who lived in London from 1721, was an assiduous copier, however, which furthered the propagation of Jan’s works. Jacob received £50 for a couple of copies which were subsequently sold on more than one occasion as original works by his famous brother.21 The British Museum has two volumes containing several hundred drawings by the great van Huijsum.22 Henry Fletcher (active 1715-1730) and Elisha Kirkall (c. 1682-1742) engraved a good many of them, which they then combined with other works in a Catalogus Plantarum (1730) [15]. Even today Jan van Huijsum is held in great esteem in England and his paintings fetch considerable sums [16].23

13

possibly Parry Walton after Simon Luttichuys

Still Life, before 1686

Dulwich (Southwark), Dulwich Picture Gallery, inv./cat.nr. DPG429

14

and Johannes van der Meer Jan Davidsz. de Heem

Portrait of Willem III van Nassau (1650-1702) in a cartouche of flowres and fruit, c. 1670

Lyon, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon, inv./cat.nr. A85

15

Anonymous London (England) 1730

Catalogus Plantarum [...] A Catalogue of Trees, Shrubs, Plants and Flowers, Both Exotic and Domestic, which are propagated for sale , In the Gardens near London [...] London MDCCXXX, 1730

Private collection

16

Jan van Huijsum

Flower still life in a terracotta vase on a balustrade in front of a landscape with sphinx, dated 1724

Dulwich (Southwark), Dulwich Picture Gallery, inv./cat.nr. L18001

17

Simon Verelst

Still life with a tulip and other flowers in a vase, dated 1669

The Hague, Museum Bredius, inv./cat.nr. 124-1946

Two Dutch families of artists active in England – the Verelsts and the van der Mijns – turned their attention primarily to flower painting. In the 1660s Simon Verelst (1644-1713?) and Herman Verelst (1641-in or before 1702), both sons of Pieter Hermansz. Verelst (1618-1678), went to London, where they painted portraits and flower pieces. Simon worked in the city until his death in 1721, Herman having already passed away in 1690.24 Pepys was enchanted by Simon’s art and the painter himself was very conceited about his abilities [17].25 Herman’s son Cornelis Verelst (1667-1734) and daughter Maria Verelst (1680-1744) were also portrait and flower painters, while the work of William Verelst (1704-1752), Cornelis’s son, can no longer be distinguished from that of English painters.26 The van der Mijn family of painters were mentioned earlier in our review of the Dutch portraitists. The siblings, Herman van der Mijn (1684-1741) and Agatha van der Mijn (1700-after 1776), and Herman’s children, Cornelia van der Mijn (1709-after 1772) [18] and Robert van der Mijn (1724-after 1767), continued the decorative floral style well on into the 18th century. There was enough work to go around for less talented artists, too. According to Weyerman, Carel Borchaert Voet (1671-1743) was in the service of Willem Bentinck, Earl of Portland, from 1689, working in England in winter and Holland in summer.27 Isaack Dusart (1628-1699) learned how to paint flowers on atlas in England and took this new fashion with him to Holland.28

It should not be forgotten that the two still life painters, Tobias Stranover (1684-1756) and Jakob Bogdány (1658-1724), decorated royal palaces with floral overdoors, that the German artist Gertrud Metz (1746-1793), who was brought up in the tradition of van Huijsum, spent many years in England, and that another German, J.F. Hefele (active c. 1690-c.1710), who arrived in England with William III’s troops, made a name for himself with his drawings of flowers and insects. It would be unforgiveable to overlook the queen of flower painters, Maria van Oosterwijck (1630-1693), who numbered William III among her numerous royal clients. She was in London in 1687 but probably only for a short while [19-20].29 To the best of our knowledge, ‘Juffrou Elisabeth Neal’ (active c. 1662), an English artist who paid a visit to the Low Countries in 1662, left no evidence of either her diligence or her art.30

18

Cornelia van der Mijn

Still life with flowers, dated 1762

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. SK-A-3907

19

Maria van Oosterwijck

Still life with flowers in a glass vase and butterflies, dated 1686

Kensington Palace (London), Royal Collection - Kensington Palace, inv./cat.nr. RCIN 405626

20

Maria van Oosterwijck

Still life with flowers in a vase, insects and a shell in a niche, dated 1689

Kensington Palace (London), Royal Collection - Kensington Palace, inv./cat.nr. RCIN 405625

Notes

1 [Gerson 1942/1983] Walpole/Wornum 1876, vol. 2, p. 134; vol. 3, p. 219; Bredius 1906, p. 132; Bredius 1915-1921, vol. 2, p. 623. [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] Peter Lely owned a large fruitpiece by ‘Flechier’, which appeared in his posthumous sale (Ogden 1943, p.187); Bredius surmised that this work, mentioned by Walpole under B. Flessiers, was painted by Tobias Flessiers. For Torrentius, see p. xx and RKDimages 7065.

2 [Gerson 1942/1983] Sale London (Christie, Manson & Woods) 13 March 1939, no. 31. Mezzotints after Hoogstraten's flower pictures were also published and distributed in England (‘sold by E. Cooper’) [= RKDimages 306100].

3 [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2002] See p. xxx; RKDimages 302971 and RKDimages 300753.

4 [Gerson 1942/1983] Houbraken 1718-1721, vol. 1, p. 357-358 [Horn/van Leeuwen 2021, p. 1-350-359]. His pictures occur frequently in old English collections.

5 [Gerson 1942/1983] Bredius 1934, p. 188. [Hear/van Leeuwen 2022] Indeed there are two painters called Pieter van den Bosch, but the Pieter van den Bosch who was in London in 1663 also painted still lifes. There is a 1663 dated still life once documented in the Sideroff collection in Sint Petersburg (Hofstede de Groot index card 72731).

6 [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] The painting in the Royal Collection is probably the picture shown to Charles II by Peter Lely (Shaw 1990, p. 404).

7 [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] The painting now in the Museo de Arte de Ponce contains a medallion with the portrait of Charles II.

8 [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] However, Roestraeten’s innovative focus on oriental objects has been seen as a bridging element from traditional vanitas paintings to modern still life (Shaw 1990, p. 406).

9 [Gerson 1942/1983] Collier's picture shows an illusionistically painted letter rack. One letter bears the insciption: ‘for Mr. E. Collier, Painter at London’. Unfortunately, the date on the newspapers is no longer clearly visible. [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] Gerson was familiar with the painting now in the Victorian & Albert Museum through a photograph which the RKD acquired from Sotheby’s London, where the work was sold on 11 November 1936, no. 2. At the time it was not known that Collier had been in England; Von Wurzbach and Thieme/Becker make no mention of it. Today, dozens of paintings with London inscriptions are known, thus documenting his stay in London between 1693 and 1702, as well as from 1706 onwards. Wahrman believes Collier already visited London c. 1682-1684, but this remains undocumented (Wahrman 2012, p. 117-119, 129).

10 [Gerson 1942/1983]. Similar pictures with English newspapers and with English engravings at the still life exhibition in Brussels in 1939 (Zarnowka 1929), no. 39 (from 1701) and sale London (Robinson & Fischer), 14 October 1937, no. 64 (from 1695).

11 [Gerson 1942/1983] Walpole et al. 1762/1876 (ed. Wornum), vol. 2, p. 248.

12 [Gerson 1942/1983] Von Uffenbach 1753, vol. 2, p. 496. [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] Wharman believes the painting was made by Jeremiah Taverner (active c. 1690-1733) after a lost work by Edwaert Collier, for which is no evidence (Wahrman 2012, p. 177. The only painter known to me who closely follor

13 [Gerson 1942/1983] Marquess of Lothian Collection at Newbattle Abbey; perhaps also one of the paintings acquired by Sir Robert Kerr. Hofstede De Groot 1893B, p. 216. [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] Hofstede de Groot knew the still-life from autopsy, but Gerson clearly did not; Hofstede de Groot cited the signature as ‘B FERRERS Pynx 1697’, who is to be identified as Benjamin Ferrers (active 1697-1733), not as Dirck Ferreris. The painting was auctioned in 2016 (RKDimages 306116).Dirck Ferreris was only shortly in England, probably in 1678-1680.

14 Gerson 1942/1983] Sale London (Chrstie’s), 17 May 1935, no. 127; the group portrait is dated 1660, Sale London (Christie’s, 24 November 1924, no. 99. [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] Gerson found the images in the Witt Library, London. As the material of the Witt is inaccessible at the moment, we scanned them from the Witt micro fiches at the RKD.

15 [Gerson 1942/1983] The work in Edinburgh is mentioned in Hofstede De Groot 1893B, p. 134, no. 104. A landscape with ruins in the manner of Chaerles de Hooch and Cornelis van Poelenburch was given to J.J. Ferguson [= James Ferguson] at the Syrett Sale, London (Robinson & Fisher), 29 May 1924, no. 127. Perhaps our artist is meant, as the pastels of J.J. Ferguson look quite different. [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] Gerson was correct; the painting surfaced on the art market in 1985 as by William Gowe Ferguson (RKDimages 306133). In 2000, Eidelberg attributed all landscapes with ruins by William Ferguson to his son (?) Henry Ferguson (1665?-1730), see Eidelberg 2000. Eidelberg’s theory is not generally accepted.

16 [Gerson 1942/1983] Cook 1926, no. 429.

17 [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] The painting is possibly a copy after an unknown work by Simon Luttichuys (1610-1661), a ‘master of mobility’ with roots in Germany, the Dutch Republic and Engeland. Ebert 2009, p.139; Jonker/Bergvelt 2021.

18 [Gerson 1942/1983] Houbraken 1718-1721, vol.1, p. 209. [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] Horn/van Leeuwen 2021, vol. 2, p. 209-210. However, Houbraken does not state that Willem III took the painting to England. It was listed in Het Loo palace and stayed in stadholders’ collection until it was looted by the French in 1795. As is was one of the few paintings that was not recuperated from France, it still can be seen today in Lyon. Meijer 2016, no. A 237. Bok demonstrated that Johannes van der Meer was rewarded with lucrative jobs (Bok 1998).

19 [Gerson 1942/1983] Weyerman 1729-1769, vol. 3, p. 387. [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] Meijer however assumes this must have been David Cornelisz. de Heem (1663-before 1714) instead and doubts whether Jan Jansz. de Heem was active as a painter; F.G. Meijer in Saur 1992-2022, vol. 71 (2011), p. 19 and 22.

20 [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] Weyerman 1729-1769, vol. 4, p. 435-436. On Weyerman in England: Fuchs 2014.

21 [Gerson 1942/1983] Van Gool, 1750-1751, vol. 2, p. 13.

22 [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] White 1964.

23 [Gerson 1942/1983] An interesting example of price development in the 19th and 20th centuries in Connoisseur 1938, p. 166 (concerning Hofstede de Groot 88). [= RKDimages 117529].

24 [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] Simon met Pepys in London in April 1669, but Herman came from Paris (probably with his brother Simon) to London in the early 1680. Simon did not die in 1721, but between 1710 and 1717, possibly in 1713 (P. Taylor in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 2004/2008). As Herman’s estate was auctioned in London on 31 December 1702 (Waterhouse 1988 p. 283), he probably died in or shortly before that year.

25 [Gerson 1942/1983] Pepys expresses his astonishment with the following words: ‘… the finest thing I ever saw in my life, the drops of dew hanging on the leaves, so as I was forced again and again to put my finger to it to feel, whether my eyes were deceived, or not’. Allard de la Court (1688-1755), who visited him in London in 1710, is less forthcoming about his art (De Roever 1887, p. 71). About his vanity see: Walpole et al. 1762/1876 (ed. Wornum), vol. 2, p. 114-116; Veth 1896, p. 109, where also the other Verelsts are mentioned. [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] It is unknown which painting Pepys saw in 1669. Although only few of his paintings are dated, there are two dated paintings of 1669: one in the Bredius Museum in The Hague and the one in Cambridge (RKDimages 306293).

26 [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] Although there are still many unclarities in the biographies of the Verelst family, archival research by Paul Taylor shed new light especially on the life of William Verelst, who was not the son of Cornelis, but of John Verelst (c. 1675-1734) (P. Taylor in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 2004/2008).

27 [Gerson 1942/1983] Weyerman 1729-1769, vol. IV, p. 67, 111.

28 [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] According to Houbraken, his wife [Cathatina van Valkenburg (1626-1666] daughter of a silk merchant], whom he had met in England, collaborated with him. Horn/van Leeuwen 2021, vol. 3, p. 83.

29 [Gerson 1942/1983] Houbraken 1718-1721, vol.2, p. 215; Upmark 1900, p. 125. [Hearn/van Leeuwen 2022] Horn/van Leeuwen 2021, vol. 2, p. 215-216; Laine/Magnusson 2002, p. 140. Nicodemus Tessin II (1654-1728) visited Melchior d'Hondecoeter in Amsterdam in 1687, where he saw a flower piece by Maria van Oosterwijck. She just had left for London; Hondecoeter also told Tessin that she had been a pupil of 'Chev. de Heem’. Maria’s trip to England may have been related to the two paintings in the Royal Collection. Houbraken says she received 900 guilders for a painting from William & Mary.

30 [Gerson 1942/1983] De Bie 1661-1662, p. 558; Bredius 1890, p. 7.